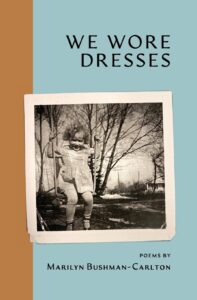

A guest post by Marilyn Bushman-Carlton about her new poetry collection, We Wore Dresses (BCC Press).

A guest post by Marilyn Bushman-Carlton about her new poetry collection, We Wore Dresses (BCC Press).

I don’t deliberately write Mormon poems so I was somewhat surprised at how Mormon my book became as the final assortment came together for this collection. Mormon, not in a moralizing sense but a cultural one. As the late Melissa Wei-Tsing Inouye says in her essay introducing Epistles to the Saints, “The Church is mostly not church. It is mostly what people do in their everyday lives and relationships.” My poems reflect the Mormon way of doing and being simply because it’s what I know. And I don’t know of any other culture that does so many things simultaneously and/or better than Mormons do.

The title poem of We Wore Dresses was not the first poem I wrote for the collection, but writing it gave me both a metaphor and a theme for the book. In the small Utah County town where I grew up, church and community bled together like a red shirt in the wash, and I do mean red as in conservative and shirt as in patriarchal. Of course, we all know the gender roles both church and society embrace and how women’s roles are most often defined by our bodies: how we, and others see, treat, and present them. We presented in dresses that defined our bodies’ uses, what we could and could not do. We couldn’t play on the tricky bars, for example, without fear of exposing underwear approximate to our girl parts. For boys, too, it was taken for granted that they embrace their boy roles. Those roles can be glimpsed in my book as well.

I like to think of girls confined to wearing dresses as the score in the background of my formative years. And that score, of course, has played on and on throughout my long life. In poems it plays as I work at jobs rather than go to college, as I marry, have five children in quick succession, am a stay-at-home mom. It plays in what I eat, how and what decisions I make, and behind my role as wife of an attorney.

The second phase of the Women’s Movement began at about the time I married my childhood sweetheart, and to both of us, equality made perfect sense. Society was beginning to change for both women and men, and we welcomed what some in the church considered radical ideas. Some of the poems show both my struggles to define myself and my husbands’—the back and forth of establishing equity in a partnership that gives primacy to both his profession and overall importance.

Although I’d embraced motherhood and homemaking wholeheartedly, a light came on when I read Betty Friedan’s description of “the problem with no name,” (The Feminine Mystique), the persistent feeling that something, a big something, was missing in my life. I had no idea who I was or what I needed. It was my husband’s suggestion that I go to college, and with his full support and encouragement, I became a student for the first time at the University of Utah the same year our youngest child began kindergarten. I knew my family could not be secondary, but I also knew I wanted an education badly and would give it my all. The pressure was on. My ability to take classes was a family thing—everyone had their jobs—that usually ran as smoothly as a lunch line.

The earlier poems in the collection have an edge as I look back at a time when I was actually exquisitely happy. I’d loved my formative school years, loved being a girl and living in a girl world with its intimate girl friendships. I enjoyed playing jump rope and jacks and had no desire to do boy things like sports. I’d had no idea that even then, as a female, I’d been considered secondary and had been “put into a dress” to keep me in my prescribed role.

Simone de Beauvoir (The Second Sex) says that “One’s life has value so long as one attributes value to the life of others by means of love, friendship, indignation, and compassion.” I love how she slipped indignation in among the expected womanly things. I cringed when I began to date and boys felt the need to show me how to hold a golf club or throw a bowling ball. Or when my husband-to-be insisted that I agree he would make the big, final decisions (I finally agreed but my fingers were crossed.) Again, from Beauvoir: “To make oneself an object, to make oneself passive, is a very different thing from being a passive object.” From as long as I can remember, I’ve recognized each and every insult to my full humanity, and that shows up in my, sometimes snarky, writing. Mostly it shows up in the poems about my growing-up years as I look back at that time with the wisdom of experience.

Of course, I spent most of my life adjusting my schedule to my husband’s, writing at home as I managed the household, both occupations not easily identified; and the latter unending. I reclaimed my maiden name with a simple hyphen, and began telling my story. I found my identity by writing myself into existence.

Like Mary Cassatt and Berthe Morisot, my art often originates from my world at home, where I try “to catch the fleeting moment—anything, however small.” (Morrisot) My family are ready subjects. My poems are about what I did, and do: being in a marriage and being a mother, often musing about whether I did this or that thing right. In “Music Comes for the Oldest Son,” that son “comes to the symphony lugging his polished shoes, his pockets bulging with woe,” while I worry he is “bankrupting [my] best efforts to indulge [my] vanity” as I’ve gussied [the five children] to flawlessness.” About that same son, I wonder in a poem after the fact how my feminism might have affected his early years.

The dress is like wearing a sign or a logo that says “girl.” It decrees what paths we follow, how we envision ourselves. It insists that some things don’t come in your size or shape. It says the things on this side of the room are okay for you to use, but don’t touch the things on the other side. It says you are hobbled from even seeing yourself in a variety of roles. What executive wears, at least in my time, a (symbolic) dress, who, wearing one, climbs a mountain or presides in church?

Nevertheless, I love being a woman and hope that is evident in my poems. And, although I have some regrets—the biggest being that I didn’t go on to graduate school, even at the coaxing of an admiring professor who would have waived the requisite entrance exam— I was just too exhausted—I am a satisfied, happy, old (in age only) woman. I write poems about my continuing relationships with my children and, now, grandchildren; about the continuing interchanges that happen with married couples who never get it entirely right. I hope readers of We Wore Dresses can find themselves in my poems, in the celebration of an ordinary life.

We Wore Dresses

We wore them everywhere. Learned the lay of the land

in them. They reigned in our closets

Every day to school we wore them. On the tricky bars,

stifling the urge to hang from the natural

bend of our knees

Scenting starch and cotton, we learned division in them,

in sashes and wide hems, diagrammed sentences,

driving pencils—

our legs crossed stony tight because of them—

down the dead-end streets

where prepositional phrases and adverbs belonged.

In dresses we were careful, won few scars or bruises,

collected even fewer tales of swift licks, shattered bones.

No scrabbling to the rescue in a dress,

or scorching to home base. We played jacks

with bouquets of skirt bunched

in the V of our legs. Dresses covered

intricate bodies: puffed-sleeve dresses, dresses

with gathered skirts, pleats like Japanese fans.

We were flowers: angel trumpets, fuchsia, inverted tulips.

Lithe teenage bodies in baby dolls, twirly skirts, sheaths.

We were lavished with long, elegant versions

for balls and proms—

satin and glitter, chiffon and shine.

How exquisite we felt—our throats bared and blushed;

the way, with our fingertips, we lifted the skirts like ladies.

How disarmed we were,

our soft flesh belted,

an orchid stuck near our made-up faces, perfumed

and pinned carelessly close to our hearts.

Marilyn Bushman-Carlton received a BA from the University of Utah (as a mother of five) in 1989. She has previously published three poetry books: on keeping things small (Signature Books, 1995); Cheat Grass, (Utah State Poetry Society, 1999), which won the Pearle M. Olsen Book Publication/USPS Poet of the Year award; and Her Side of It, (Signature Books, 2010), winner of the Association of Mormon Letters Poetry Award. A chapbook version of Her Side of It was a finalist in the Comstock Review’s 2005 Jess Bryce Niles Chapbook competition. She has also authored a book of children’s poems, Pulchritudinous and Other Ways to Say Beautiful, for her sixteen grandchildren, (Lulu Press, 2015).

Marilyn Bushman-Carlton received a BA from the University of Utah (as a mother of five) in 1989. She has previously published three poetry books: on keeping things small (Signature Books, 1995); Cheat Grass, (Utah State Poetry Society, 1999), which won the Pearle M. Olsen Book Publication/USPS Poet of the Year award; and Her Side of It, (Signature Books, 2010), winner of the Association of Mormon Letters Poetry Award. A chapbook version of Her Side of It was a finalist in the Comstock Review’s 2005 Jess Bryce Niles Chapbook competition. She has also authored a book of children’s poems, Pulchritudinous and Other Ways to Say Beautiful, for her sixteen grandchildren, (Lulu Press, 2015).

Her prose includes a biography, Worthy: A Young Woman from a Background of Poverty and Abuse Falls Prey to a Polygamous Cult (Lulu Press, 2016), a finalist for the 11th Annual Indie Excellence Award.

Other awards include a prize (1997) and a grant (1996) from the Utah Arts Council, for whom she was an Artist-in-Residence, traveling throughout Utah to teach poetry in elementary, middle, and senior high schools (1996-2012); and awards for individual poems from the Comstock Review, the Ledge, The Sow’s Ear, BYU Studies; Utah State and National Poetry Societies, Red Butte Gardens, UTA Poetry on the Bus, and others.

Individual poems appear in Dove Song: Heavenly Mother in Mormon Poetry; Fire in the Pasture; Twenty-First Century Mormon Poets; Discoveries: Two Centuries of Poems by Mormon Women: SLCC Anthology (2018 and 2020); Utah Sings (Vols. 7, 8, & 9); and other anthologies.