Review

———-

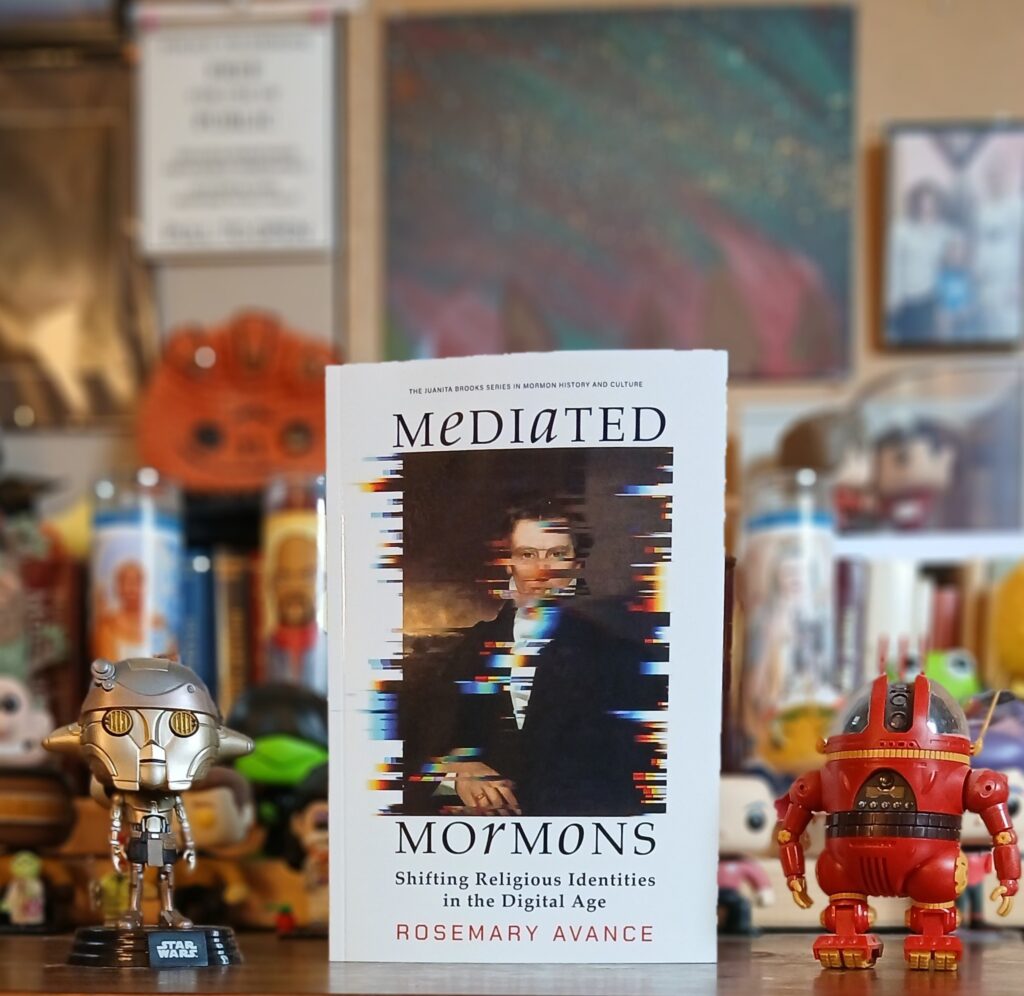

Title: Mediated Mormons: Shifting Religious Identities in the Digital Age

Author: Rosemary Avance

Publisher: University of Utah Press

Year Published: 2025

Pages: 214

ISBN: 9781647692063

Genre: Sociology of Religion

Price: $29.95

Reviewed by Michael Hicks for the Association for Mormon Letters

As one ages, one sees in history fewer moments and more brushstrokes. Just so, at my age, the notion of a “Mormon moment” seems quaint and contrived. Just a whistlestop from the afterlife, I’ve reached that Solomon-esque view that there’s nothing new under…. you get the idea. But, buying into the putative singularity of a “Mormon moment” in early 2010s America, I was eager to survey and assess this study, which focuses on that alleged moment but sprawls wider in its inferences.

The good news is that it was worth the sometimes-muddy trip. The bad news: none, really, except for the regret—read “hope”—that this book is a mere signpost for further excursions on the path it treads.

The best takes on Mormonism often come from “outsiders,” the unbaptized (or estranged) non-Utahns who point a less clouded, though differently tinted, lens onto the subject. That holds true here. Via chapters on caffeine, Mitt Romney’s alleged heresy, and patriarchy, Rosemary Avance burrows well into patterns of Mormon image fixation and transformation. Lots of good to be mined in these chapters, which, in my mind can be sampled (or skipped) in whatever order and proportions one chooses. (The strongest, to me: the Chapter 4 exploration of bona fide internet-based warfare among orthodox camps and their opponents; the weakest: Chapter 3’s take on Mitt Romney’s presidential campaign, which flourished, in my view, mostly in old-school media, from billboards to network talk shows—even Utah priesthood meetings.)

As an old McLuhanite-turned-Barthesian (with a lot of Sontag thrown in), I missed in this book some of the pithier prose and theory, however intuitive, that would have made the writing bristle more with insight. I sometimes felt as though I was reading through frosted glass. The best of the book comes in the well-paced storytelling, some firsthand, and resonant with good journalism. The worst of it comes in the dissertationese jargon that swells through about half of the book. Now, I do recognize that readers’ appetites differ. One reader’s meat is another reader’s gristle. Take either with a grain—or pound—of salt, noting that both are in themselves different “identities” in the clan of Mormon readership.

I do have various “noted with pleasure” moments in the book. I loved the author’s formulation of “devil word,” used on at least two occasions, a nifty three-syllable compound of idea-cum-impulse. Or her description (p. 62) of Mormonism’s “founding myth” as “the incarnation of the American dream . . . an uneducated plowboy innovating religion from the dust,” etc. Or her definition (p. 105) of “patriarchal order” as “a Mormon phrase . . describing God’s eternal structure for both temporal family life and ecclesiastical hierarchy, as well as the eternal structures of the cosmos.” And even—maybe especially—her heading on p. 58: “The Digital Fractures of Mormon Imagined Community,” which may be the best summary of the book’s core topic. (I’d have used it in, or even as, the title of the book.) These and other readerly “moments” are worth combing out and saving.

Still, I kept asking myself, “Is this book too little too late, or too much too soon?” On the latter question, the book may dwell too wordily on a minuscule slice of the calendar. (I feel the same about all treatments of the “September Six,” which was a coincidental confluence—however deviously mapped out by Packer, et al.—in the rapids of a river that had been raging for decades and did so long after.) (Sorry for that digressional “moment”!) But to put a microscope on a bit of cellular tissue often illuminates another glimpse of different tissue years later. As always, time will, if not tell, at least tease us with the promise of disclosure.

On the former question, I kept looking for cross-references to earlier transformative technologies of Mormondom (from newspapers to radio) or potentially more pertinent test cases (like spiritual pugilism over R-rated movies or tattoos and body piercings). I also missed cross-references to the work of, say, myself in Sunstone articles and columns in the 1980s re: media massaging of Mormonism, or the voluminous work of the maestro in the field, Jon Durham Peters (cited only for one article in the book’s bibliography).

But that’s carping. Let me close with two thoughts from an old guy’s flyover coordinates.

First, in another “noted with pleasure” passage, the author writes that, in the digital age, “the institution and vernacular communities have engaged in a virtual dance in historic Mormon fashion: expand, then contract; concede, then retreat” (p. 154). But I see digital media as widening, beyond measure, the dance floor. The notion of Mormon community began with the recalcitrant pose of its founder, Joseph Smith, who, as a boy, famously told his mother, “I can take my Bible, and go into the woods, and learn more in two hours than you can learn at meeting in two years if you should go all the time.” That conceit expanded, moment by moment, brushstroke by brushstroke, into the global, trans-mediated but real estate-mapped faith community of today.

Now the internet has essentially—that is, literally, of its essence—re-carved the old geographies into “imagined communities” that are spading up the grounds of ecclesiastical maps. I myself, for example, have hundreds of “friends” on Facebook, who offer true companionship on a common, though hard to define, Mormon path. I wouldn’t think of inviting most of my tangible friends in our neighborhood-drawn ward into my virtual Mormon religious community. My Mormon neighbors and I are on the same path, yet on different paths. Which the internet did not so much dictate as revealed. Because that technology has created new “wards” and “stakes” and “regions” and “areas,” ungovernable except by whatever branding or charisma presides in a bouncy community whose dance floor aspires to infinity. “Who is my neighbor?’’ Jesus rhetorically asked. The internet now answers: “Seriously, you have no idea.”

Which leads to a second thought. The internet itself is not just the platform for the skewering of Mormon identity. It is itself a new spiritual identity. Mormons, like the humanity that both surrounds and inhabits them, have found in digital technology a pocket deity to which one turns for answers at the drop of a question. Arthur C. Clarke’s maxim is the credo: “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.” That magic, like most magic, metamorphoses into religion—or at least irrevocably recasts whatever religion still waits in its wings.

That I can discuss heartily such ideas after reading this book certainly honors the book beyond any of my small misgivings. So, my flyover take is: Mediated Mormons forms a worthy précis of vaster work that will put its arms around conversations some of us have been having for decades—and must keep having. It’s a small but hyper-detailed sermon about transient winds of change that, in time, are fiercely determined to become eternal.