Review

———-

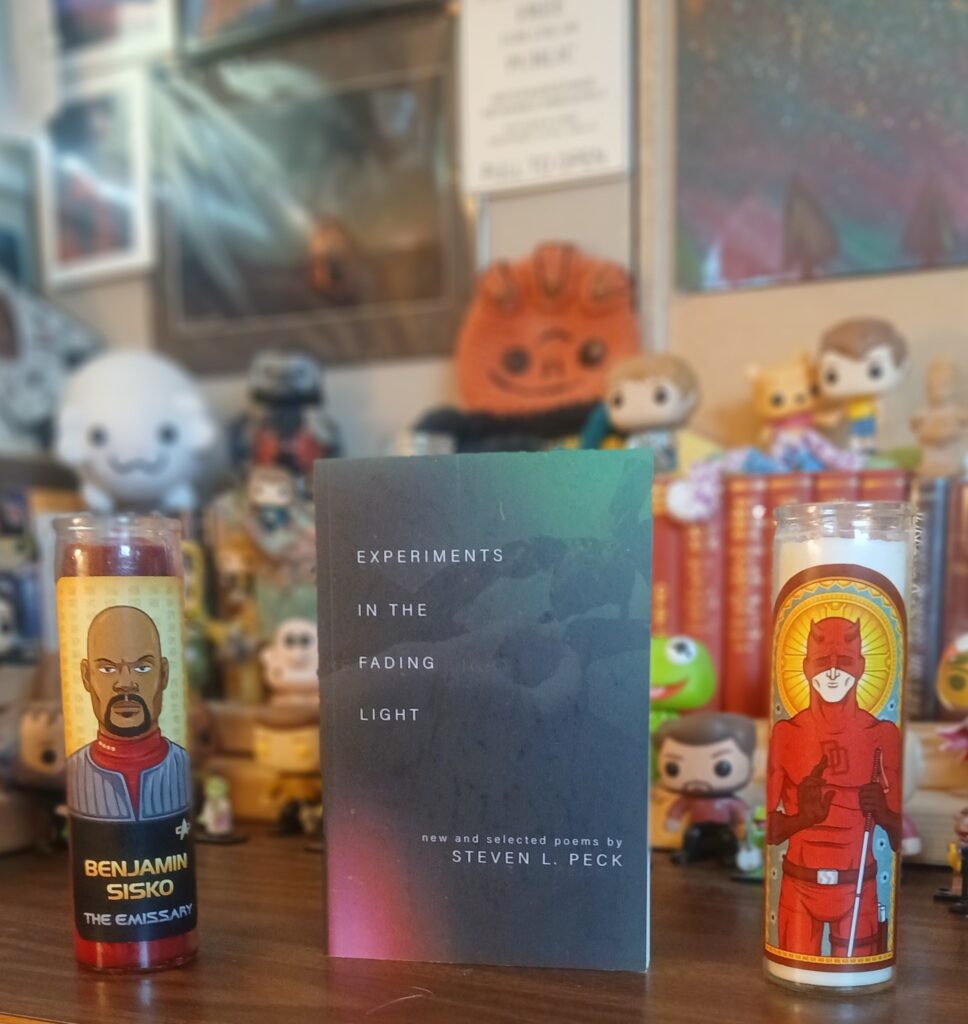

Title: Experiments in the Fading Light

Author: Steven L. Peck

Publisher: Signature Books

Date: 2025

Pages: 134

ISBN: 978-1-56085-520-0

Cost (paperback): $19.95

Reviewed by Julie J. Nichols for the Association for Mormon Letters

If you’ve read anything by Steven L. Peck, you will not be surprised to hear that the collection of poems in Experiments in the Fading Light is many contradictory things: inquisitive and intellectual, but heartful and readable, sometimes formal and often formless, much more a brilliant child exploring a delightsome medium than a studious artist fulfilling his personal Statement of Purpose. I could sometimes wish Peck were a little more consistent formally. But he’s blessedly consistent content-wise.

The collection (of “new and selected poems,” so you may have read some of these elsewhere, though the only one I remembered was “My Mother Became Chatty at St. Marks”) is divided into nine “investigations.” These are sections of irregular size and shape. All begin with a line or two from William Blake, himself one of the more blessed poets of the world. Allusions and responses to other great world thinkers abound.

The first investigation, “Experiments in possibility,” consists of twelve pieces. “Additions to St. Hildegard’s Physica” is a lengthy prose poem defining, as per Hildegard von Bingen, such flora and fauna as deer, aspens, and Vesper bats. Other selections have possibility-musing titles like “Sparrow People,” “If you were a Tree,” and my favorite in this section, “Non-Art.” This last is downright funny, imagining a museum full of the things the poet has never painted. Can’t we all relate to that imagining? Wouldn’t it be great to see a showcase of all that we haven’t accomplished, gushed over by learned critics and happy fans?

In his acknowledgments at the end of the book, Peck graciously lists many and sundry influencers, writers, and teachers, famous and less famous, who have helped him explore what being a poet means. Starting with this first section, we see how their examples and philosophies enable his personal probings, his own quests into the possible, the only too probable (climate change and ecological disaster), the beautiful (art), and the cosmic.

The second investigation is “twenty-two observations on the climate of my warming backyard,” twenty-two small vignettes, not complicated, answering the call of his poet mentors to use all his senses and then to recreate perception in words. Very nice. The themes of this section are picked up in sections (“investigations”) six and nine, “ecological field observations” and “on a threatened planet.” Again, if you’ve read anything by Peck, you know his ecopoetics: science informs his heart and spirit, and vice versa. Capitalists and technophiles beware. The natural world is bigger than anything.

A few quotes:

From investigation eight, “experiments in a theology of grace”:

“PRAYER”

Once years ago

I started to wonder if God

ever did anything for me

So I told him I was going

to do an experiment

“I’m going to stop praying”

And so I did…

And the blessings

or the lack thereof continued

apace as they always did…

I still pray now and again

when in real need…But when I make a

choice now I feel God shrug…

I sense him saying

“Do stuff You’re here to

learn Keep learning” (106-107)

You’ll like to read the whole poem. I gave it an extra star. It said truth to me.

Another quote, from investigation three, “Quantum experiments with the Odyssey”:

“Odyssey/Dover Beach Two-Slit Wave-Particle Optical Refraction Experiment”

[Odysseus is dreaming]…

He was at home. Telemachus was there,

a child again. No more than eight, yet dressed

as if for war. In his right hand a small dory,

and on his left arm an aspis, round and well-

made….

…through narrow slits Odysseus can see the child’s eyes wide, questioning—one

eye filled with terror, the other hate…

And as the boy looks at his scarred father, he says something…

the voice tinged with longing

and woe, a fading sigh in hopes unrealized.

[Odysseus] looks

over the glass-like sea and pulls his aging fists into his

empty belly, swears by Zeus’ aegis there must be more

to life than war and blood and sorrow and the distant

sound of pebbles grinding endlessly in the waves. (49)

Perhaps you can see just from these two examples (which are not complete and don’t show the actual shapes of the poems) how varied are Peck’s investigations, how widely he travels the universe experimenting and investigating not only its eternal questions but also the varied forms of its inhabitants. Perhaps Experiments in the Fading Light has a melancholy title, but it is not a melancholy collection. It’s alive, interesting, and an exercise in “read-pause-think,” as Karen Austin says in her Segullah review of Gilda Trillim. This is what we’ve come to look for in Steven L. Peck’s work, and it’s warmly welcome everywhere it shows up.