Review

======

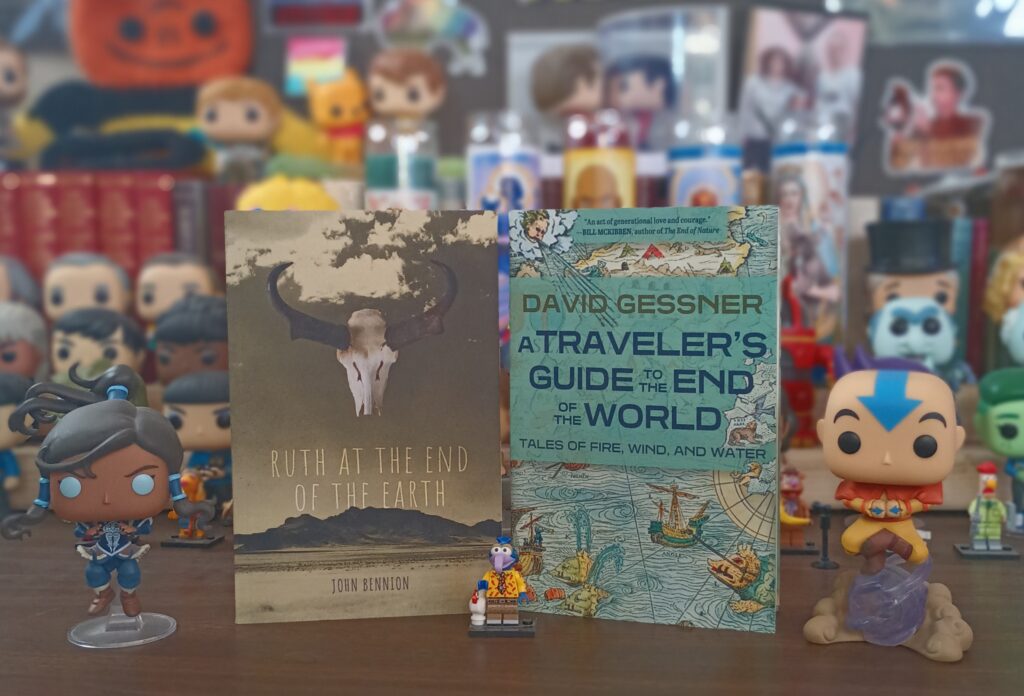

Title: A Traveler’s Guide to the End of the World: Tales of Fire, Wind, and Water

Author: David Gessner

Publisher Torrey House Press

Genre: Non-Fiction

Year Published: 2023

Number of Pages: 320

Binding: Paperback

ISBN: 978-1948814812

Price: 16.99

Title: Ruth At the End of the Earth

Author: John Bennion

Publisher BCC Press

Genre: Fiction/Novel

Year Published: 2023

Number of Pages: 450

Binding: Paperback

ISBN: 978-1948218948

Price: 13.95

Reviewed by Julie Nichols for the Association for Mormon Letters

The End of the World, twice

A review essay about

- A Traveler’s Guide to the End of the World: Tales of Fire, Wind, and Water by David Gessner (Torrey House Press 2023)

- Ruth At the End of the Earth by John Bennion (By Common Consent Press 2023)

- Other books discussed or mentioned in this review essay:

- Silent Spring by Rachel Carson (1962)

- The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History by Elizabeth Kolbert (Holt, 2014)

- This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. The Climate by Naomi Klein (Simon & Schuster 2014)

- The Uninhabitable Earth: Life After Warming by David Wallace-Wells (Tim Duggan Books, 2020)

- Otherlands: A Journey through Earth’s Extinct Worlds by Thomas Halliday (Random House 2022)

- Fire Weather: A True Story from a Hotter World by John Vaillant (Knopf 2023)

You must know by now that the world is coming to an end. There’s a howling clamor, an entire library of books and articles, podcasts and documentaries, laments and arguments about it.

This clamor didn’t start with Rachel Carson, but maybe it came into our consciousness in its current incarnation with her 1962 Silent Spring. In the sixty years since then, awareness has surged, and now everywhere we turn, we can read The Sixth Extinction, Fire Weather, The Uninhabitable Earth: Life After Warming, and Climate vs Capitalism—all titles in this ever-growing collection of warnings about what’s coming. Not to mention their equally vigorous and strident opponents. But it’s not the opponents we (or at least I) hear the most. Most of us don’t deny what’s happening, but we need help managing the breadth and depth of its implications and our part in it.

Should we blame Big Oil? Should we keep a tally of the people we know whose homes, lives, and families have been upended, including our own, by disaster and disease? Do we buy a hybrid car, travel only by bicycle or on foot, make ourselves a tiny house, become vegan? Or should we go on as we always have, kicking the can down the road, burying our heads in the increasingly dry sand, the increasingly burned-over or flooded landscape?

Here, to address these questions, are two surprisingly similar, though generically different, approaches to our present catastrophe, identifying it as precisely that: a catastrophe we need to face with intelligence and wisdom.

John Bennion’s Ruth at the End of the Earth embodies the imaginative approach. This is a dystopian novel whose grim world rakes us in by the power of its strong, wise, hopeful protagonist. She lives in a future world (2135, Bennion tells me) that Americans of the West—Utahns—can easily recognize. In a cave in a desert ravaged by fire, whose human and nonhuman inhabitants are desperately and constantly in need of water, Ruth lives with her community, a small family whose life is defined by survival protocols: what to drink, what to eat, what to forage, when not to go outside in the blazing sun, when to move to the next living place. Into this world stumbles a man from a city (Salt Lake? Las Vegas?) with a city-dwellers—a capitalist’s—beliefs about survival. That is, money and machinery, and selfish power; will ensure the survival of those lucky enough to have them. Ruth doesn’t agree, but she loves her people and feels called to leave her community to go with this man on the chance that his plan to bring long-term survival in the form of a water source might actually work.

Meticulously, ruthlessly imagined (the name “Ruth”—“pity or compassion, sorrow or grief”–is no coincidence), their journey does not succeed. People they love die in the course of their journey. Ultimately, they cannot win.

This isn’t a spoiler. The name “Ruth” also alludes to the woman of that name in the Bible, who reaches out to those not of her tribe to say, “My people shall be your people.” Bennion’s Ruth does this too, in a twenty-second century way. You need to read the book to see what Bennion imagines might happen when greed and xenophobia meet deep heart sense in the midst of the apocalypse. I recommend that you do.

Bennion’s imagining joins dozens—scores—hundreds of voices keening our impending demise as evidenced by the very real fires, floods, wars, and weather hurtling our planet and its inhabitants toward a rapidly approaching end.

“Rapidly approaching,” for David Gessner, author of Torrey House’s A Traveler’s Guide to the End of the World, means his daughter’s lifetime. Specifically, the year she turns his present age, forty years from now: 2063. He asks experts in fields from coastal geology to firefighting to law: what will our world, this region, this town, this neighborhood look like in 2063? And what’s to be done to make it habitable for my daughter?

Over and over, the answer is: it won’t survive. Don’t try.

This book is a fine hybrid of literary and data-driven approaches. It’s a highly readable, sometimes even (thank God) humorous travel/memoir/lament in which Gessner travels to the Outer Banks of North Carolina to experience the consequences of hurricane and coastal erosion, to New Jersey and New York City to experience the consequences of urban weather of increasing intensity, to Colorado to experience the consequences of fires in the west. He interviews field scientists, quotes poets, and calls in information from agencies across the nation. The consensus: there’s no help for it. Get out while you can.

Well, not completely. Over and over Gessner confesses his own complicity, giving in to the temptation not to think about it, to attend to the opposition, or simply to ignore the signs. As he does so, he also makes it clear that every choice we make—“we” meaning you and I, but even more importantly our institutions, industries, policymakers, and leaders—every choice our species makes, individually and collectively, influences the timing and nature of our end. For Gessner this is not only a matter of imagining, but also a matter of attentiveness to data and common sense, here and now. We need both Bennion’s imaginative approach and this practical one if we are to wake ourselves up.

In Otherlands, which is not precisely about our current catastrophe, Richard Halliday describes not one but sixteen ends of the world—ends of worlds built upon this planet, mostly without human involvement, worlds full of creatures you and I have never seen. Crucially, his purpose is to show, through data, that every time a world has ended, the planet has survived. “We have [had] a new world here,” as the LDS Creation story would have it–a “brave new world, that has such [creatures] in’t,” as per Shakespeare.

Otherlands isn’t an antidote to Bennion or Gessner but a different perspective. Both Bennion and Gessner foresee an uninhabitable world, or a world barely habitable by people like us, if we don’t change our mindsets radically and soon. Halliday’s approach is a long view, the data-proven truth of the cycles of extinction, death, and regeneration. “We” doesn’t mean only you and I, 21st century First World individual citizens. It means all beings who’ve ever been on earth—microscopic beings, plants, animals, water, air, fire, stone, ice, stars, weather. All of it will end, has ended before, and is ending now. End times are nothing new.

If the message of Otherlands is that the world has ended multiple times and has always come back transformed, the message of Gessner’s Guide and Bennion’s Ruth is that we can make a difference through our choices in when and how that happens.

Did the nonhuman inhabitants of previous epochs make conscious choices toward their worlds’ downfalls? Dinosaurs, microorganisms, ferns, tendrils, fish? We can’t know. But we can make choices. Here’s where our stories about agency come in. Here’s where Bennion’s fable (is it a fable?) comes in, and Gessner’s journeys to sites of disaster throughout the United States: they require us to consider our choices, past, present, and future. Stories are about choices. Stories store learning and wisdom; stories are where learning and wisdom become crucial ingredients in the end-times stew we’re stewarding. We can make choices that help determine the when and the how of our end and our new beginning, for ourselves and for all that comes next. Read these books. Imagine, act, embrace. Farewell—and hello. We are none of us exempt.