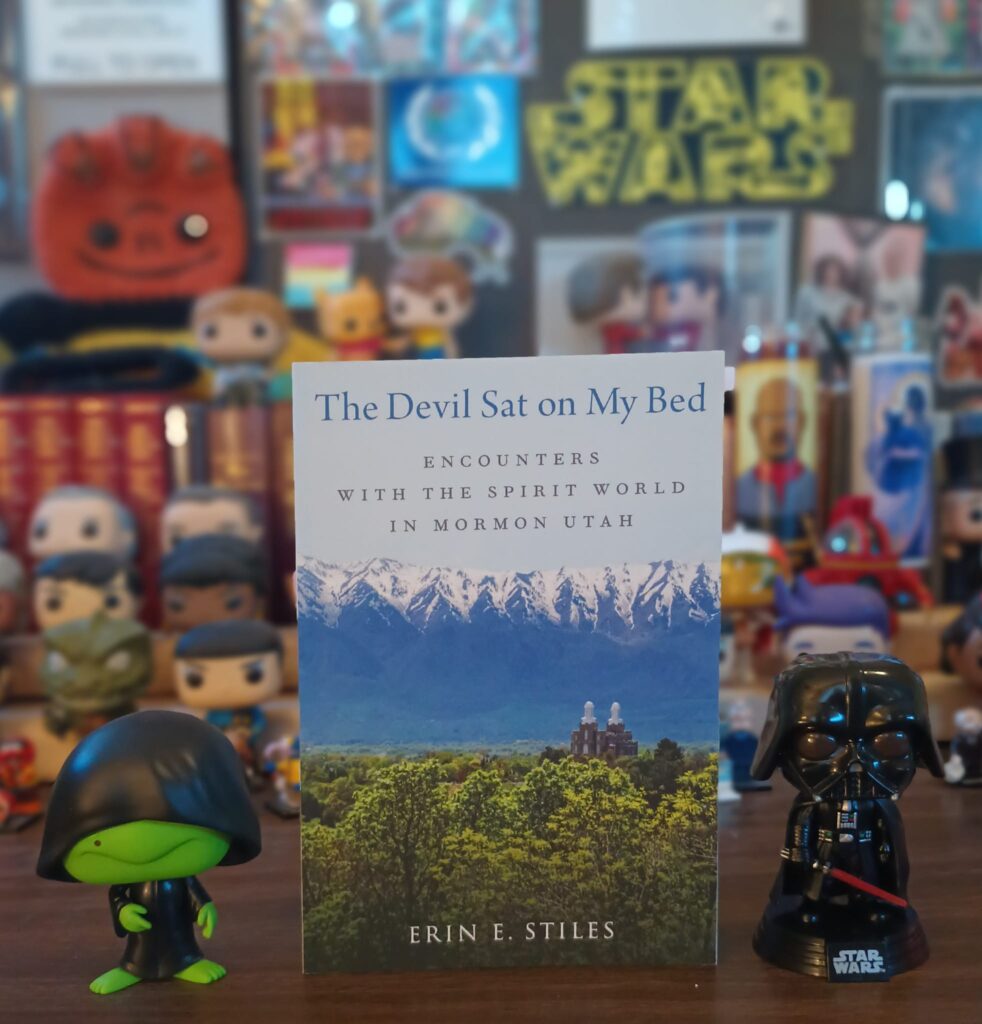

Title: The Devil Sat on My Bed: Encounters with the Spirit World in Mormon Utah

Author: Erin E. Stiles

Publisher: Oxford University Press

Genre: Ethnography / folklore research

Year Published: 2024

Number of Pages: 224

ISBN: 9780197763759

Price: 29.95

Reviewed by Monya Baker for the Association for Mormon Letters

In The Devil Sat on my Bed: Encounters with the Spirit World in Mormon Utah, author Erin Stiles is quick to explain that the account that inspired the title of her book is atypical. If a Latter-day Saint comes in contact with a malevolent spirit, it probably won’t be a distinct individual. Any identifiable spirit is almost guaranteed benevolent, and probably a relative.

Stiles, a professor of anthropology at the University of Nevada, Reno, is a non-LDS individual who grew up in northern Utah’s Cache Valley amidst LDS beliefs and lore. Her past ethnographic work centered on Islamic courts in Zanzibar. In her latest book, she interviews acquaintances in her hometown and draws from archived accounts maintained by Utah State University in Logan.

It was both jarring and enlightening to see familiar narratives framed through an anthropologist’s lens. Her phrase “posthumous baptism by proxy” lacks the sense of service conveyed by the LDS phrase “baptism for the dead.” But I liked the term “cultural kindling,” for how shared understanding and stories shape how people within a community explain their experiences. For Mormons, that cultural fuel is “collective ethical responsibility.” Spirits are not, as one interviewee explains, “just saying hi.” Benevolent spirits arrive to help others, especially kin, achieve their spiritual potential. Malevolent spirits, who can never have earthly families, have the opposite goal.

Either way, spiritual encounters have a purpose. Or, as the anthropologist puts it, “spirits are always connected in some fashion to the necessity of mortal life on Earth for spiritual progress toward salvation.” Though I left the Church decades ago, I still feel compelled to frame any pursuit as a means to progress rather than simply as an activity for its own sake. Stiles’s book helped me understand why that itch goes so deep.

Stiles has numerous examples of spirits offering guidance. A deceased grandmother warns her daughter that her teenage son is in danger. A grandfather’s spirit reassures a young man doubting whether he can complete his missionary service. Stiles explores the idea of a sort of “economy of spirits” that dictates who appears to whom. Encounters with Jesus and Joseph Smith are possible, and Stiles recounts a couple. Generally, though, visits between living and nonliving are with family, reflecting their greater likelihood of influence and interest.

Nonliving relatives also intercede beyond simple guidance. In one account, critically hospitalized Mary finds herself in the spirit world and protests that she can’t die because she still needs to take care of her husband and children. The spirit of her mother then says she’s obtained permission for Mary to live. In another striking account, a woman describes being found inexplicably safe in the back seat after the front of the car she’d been driving was crumpled in a collision. Years later, her four-year-old son, who’d never been told about the accident, sees a photograph of the scene and recalls pulling his future mother to safety.

Usually, when preborn spirits visit, it is to tell their future parents that they are anxiously awaiting their birth. “Why are you leaving me out?” one asks. One of Stiles’ interviewees sees children in a dream and recognizes them as her future children. It prompts her to break up with her then-boyfriend, who would be an inadequate father.

Several interviewees tell Stiles that they are sharing their experiences for the first time. A person’s righteousness and need for intervention govern whether a spirit can visit, which renders such stories simultaneously bragging and confessing (and, so, awkward.) But the interviewees also seem to doubt whether they will be believed. Indeed, they are skeptical of others’ narratives, which they sometimes ascribe to a need to provide comfort or feel important.

Before reading this book, I hadn’t appreciated how the LDS theology makes people interdependent for their salvation. Those born into Mormonism rely on their parents to receive a physical body. Also, the vast majority who die without being Mormon need others to physically perform the rituals necessary to enter the Celestial Kingdom.

That explains why a particular sort of spiritual encounter happens in temples. The spirit, usually a stranger, is the one being helped. “Those who experience visits in the temple tend to see them not as guidance, but as confirmatory,” Stiles writes. Grateful spirits arrive to watch their rites performed and to ensure their rites are completed. Sometimes they appear outside the temple to provide emergency babysitting help or rescue children whose parents are busy performing temple ceremonies on their behalf. Such visits, Stiles says, “index the reality of the eternality of the family as well as the righteousness of the ritual action and the ritual performer.”

Malevolent spirits, in their own way, do the same thing. Denied physical bodies after rebelling against free agency, malevolent spirits are both attracted to unrighteous acts and to exceptionally righteous souls, whom they delight in harassing and distracting from correct behavior. Stiles’s accounts of malevolent spirits are rather tame for anyone who has seen The Exorcist, and she states plainly that others might easily attribute some experiences to sleep paralysis or night terrors. (In fact, another AML reviewer suggests that the most dramatic account—a female voice whispering a missionary’s first name—could well be attributed to sexual frustration.)

Still, these accounts are fascinating for their insight into LDS ideas of evil. Anthropologists classify ideas of evil as either a human phenomenon or as resulting from a “cosmological force.” But I think the LDS view braids these ideas: the cosmological force comes from our brothers and sisters in the pre-existence who act out in anonymous grievance.

Evil spirits also serve a purpose. Since bishops and other high-ranking leaders are often called on to cast out evil spirits, Stiles explains, they offer a way for righteous priesthood holders to demonstrate authority. She relates accounts from three countries in which a missionary is healed by a shaman or someone without proper authority and is then ‘blessed’ by their mission president to reinstate and (sometimes) reheal the injury.

The notion of proper authority is as much a part of cultural kindling as the notion of mutual obligation and support. Two missionaries Stiles interviews meet only under the auspices of the mission president; deceased relatives seek permission for injured relatives to continue to live; and the rites performed in the temple are recognized because they are performed under the appropriate priesthood authority. Several interviewees assume that spirits obtained permission from heavenly authorities to make earthly contact.

But this kindling carries splinters. Stiles explains that her interviewees distinguish between Mormon or Utah culture, the institution of the Church, and the “true meaning” of the faith. The notion of authority is where schisms are most prominent. Several of her interviewees feel cultural and institutional norms have diverged from the true faith, and cite earlier history when women had more authority to take on healing and other rites. Spirits generally exist to nudge things to how they are supposed to be, so the disconnect between what is practiced in the Church and what interviewees think should be feels potent.

It also feels underexplored. I wish that Stiles had spent more time considering how spiritual encounters and attached meanings have changed over time, particularly in the early Church. But in Stiles’s analysis, an experience from the 1980s carries the same weight as one from the 21st century. Overall, though, I found Stiles’ account illuminating. It is all too easy to misjudge other cultures. Here, an informed outsider’s eye can spot patterns that an insider’s glazed gaze overlooks.