Title: True West: Myth and Mending on the Far Side of America

Author: Betsy Gaines Quammen

Publisher: Torrey House Press

Date: 2023

Pages: 318

ISBN: 978-1-948814874

Format: Paperback

Cost (paperback): $19.95

Reviewed by Julie J Nichols for the Association for Mormon Letters

If there’s a fault in this well-received second book by historian and conservationist Betsy Gaines Quammen, it might be that there’s just too much in it. In a talk at the Great Falls public library on December 7, 2023, she describes its genesis and confesses that not only does it have “everything” in it, but that her husband, the noted nature writer David Quammen, teases her that she always takes a very long route to get to her point, leaving nothing out. True West can feel like that.

But maybe that’s not really a flaw.

The genesis: her first book, American Zion: Cliven Bundy, God, and Public Lands in the West, focused on the “cowboy confrontations” of the Bundy clan, which “threaten public lands, wild species, and American heritage.” A version of her thesis; it developed from her fascination with how religion affects our view of landscapes. It was published in March 2020, so she couldn’t do book tours, and when she came across Ammon Bundy (Cliven’s son) online as he led the takeover of the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge in Oregon, she contacted him to follow up on his reasoning. Sure enough, like his father he subscribed to the myth of the White Horse Prophecy, that America was destined to belong to God’s people–Mormons—Bundy’s people–just as Quammen had written in American Zion. She began to think long and hard about the various myths (a key term in True West!) driving the Bundys, driving many people in those pandemic days, myths that had driven people to the West before then too, and continuing in 2020 to tear the country apart.

Thus True West was conceived.

“What I have asked you to do over these pages is to walk with me through a myth museum,” she says at the start of her twelfth and final chapter—a “museum” of outdated and dangerous beliefs reinforced by religious conviction, capitalist desire, opportunism, media, and other complex and nuanced factors.

“Gaze upon [the] main diorama [of this museum],” she continues:

The Cowboy, Free Land. Peek at its oddities: A Guyasticus, An Algal River. Consider its anachronisms: Frontier Individualism, Wild West, Salubrious West, Blank Slate. But it’s not just the displays that should be our focus. It’s the stories of those who are browsing them. (255)

This is True West in a nutshell: the exhibits in the “myth museum,” from the myth that neither science nor law matters in the West to the myth that resources are unlimited and destined for whoever takes them and then the stories of the people whose lives have been shaped by them, for good or ill.

Each of the myths is introduced in a chapter. Quammen tells a story or two to convince us of the contemporary reality of this myth, as a myth and as a driver of culture and behaviors somewhere here and now in the American West. (She visits Montana, Idaho, Oregon, Utah, and Nevada…) In the course of each chapter, she examines the origins of the myth at hand and investigates the ways local culture has been affected by that myth’s falsities and abuses. She cites articles, references studies recent and past, and recounts historical and recent events. Finally, Quammen illustrates its modern implications and dangers entertainingly, even lovingly, through the stories of myriad real-life people she had coffee with, interviewed, became friends with, and recorded—people with strong feelings about the myths (without ever thinking of them as myths at all), who acted on them, activists on all points of the political, religious, and intellectual spectrum.

Quammen does a fine journalist’s job of making real characters out of each of these people, describing their clothes, their homes, their manner of talking, and their emotional makeup. There are at least five in every chapter. It can be hard to keep them straight. By the fourth or fifth chapter, the reader’s head is spinning. But these human stories, and the myths they embody, are layered over with the next “exhibit,” the next set of characters, in the next chapters, not forgotten, cumulatively insisting that it is myths that have driven the story of the West. Not necessarily truth.

Just one example: Chapter 6, “The Big Bad Wolf,” begins thus:

Okay, I’ve been telling you about pandemic, rebellion, politics, western history, rural pressures, cultural expressions, machismo, and strange takes on science. But wait…if you think this book is bulging with a vast variety of subjects, you ain’t seen nothing yet. Try watching Steven Seagal’s movie The Patriot… (135)

Quammen summarizes the movie in four entertaining and appealing paragraphs. “It’s a film that remade a wide range of myths about the West,” she says, “but it omitted a big one: the myth of the big bad wolf. We’re only halfway along on this tour I promised you…and it’s time to inspect the wolf exhibit.” It’s a seamless segue into this chapter’s subject.

Steven Seagal sold his Sun Ranch in 1998 to Roger Lang, whom Quammen has known since that time as a wolf-friendly rancher, a tireless advocate for the wild. Lang is on the progressive end of the spectrum of folks Quammen parades through True West. He and Sun Ranch employees Bryce Andrews and Justin Dixon worked with varying degrees of success to maintain a balance between the cows they raised and the wild wolves on their land. Quammen invokes John D. Lee (who spoke of wild animals as “wasters and destroyers”), Ammon and Ryan Bundy (who preach that mankind has full sovereignty over every creeping thing), Jaren Watson (whose torture and “smudging” of a fox is described in graphic detail), mining executive Richard Adkerson, wildlife biologist Steve Primm, and at least five other humans as well as at least three agencies and institutions involved in the controversy over wolves in the wild. The chapter ends with a glorious list of the wildlife of the American West followed by this impassioned declaration:

Amid all of them lives another species, Homo sapiens, [which, like all these wildlife species, is] also crafty and dangerous, also accustomed to taking what it wants. Unlike the others, this creature possesses the formidable capacity to reconfigure perceived reality as abstraction, distort the abstraction into an ideal, and then try to impose that ideal back on reality. In other words, to make myths.

Wolves may be “crafty and dangerous,” but they don’t deserve to be slaughtered. It’s our myths about them that say that.

And that’s only one chapter.

The great strengths of this book are its readability, its impressive research (fifty-six pages of notes, citations, and index at the end), and its unashamed bias. Ultraconservatives are represented here with fairness, even warmth. But it’s clear that for Quammen, the point—the argument her husband says she takes so long to get to—is that the beliefs held by conspiracy theorists and anti-vaxxers and gun-toting America-as-God’s-(hence our) land purveyors have been built up, with negative consequences, by films, fiction, and sensationalist media. They simply are not true.

The West is not a place of infinite space or privilege. Cowboys are not gunmen. Violence and anarchy, social or intellectual or religious, are not the way of the West and never have been. That Quammen loves the West is clear. Though there is, as I said at the beginning, a whole lot of information, imagery, human interest, and story to take in in True West, it’s all a testament to Quammen’s conviction that the West is beautiful, varied, and infinitely worth keeping.

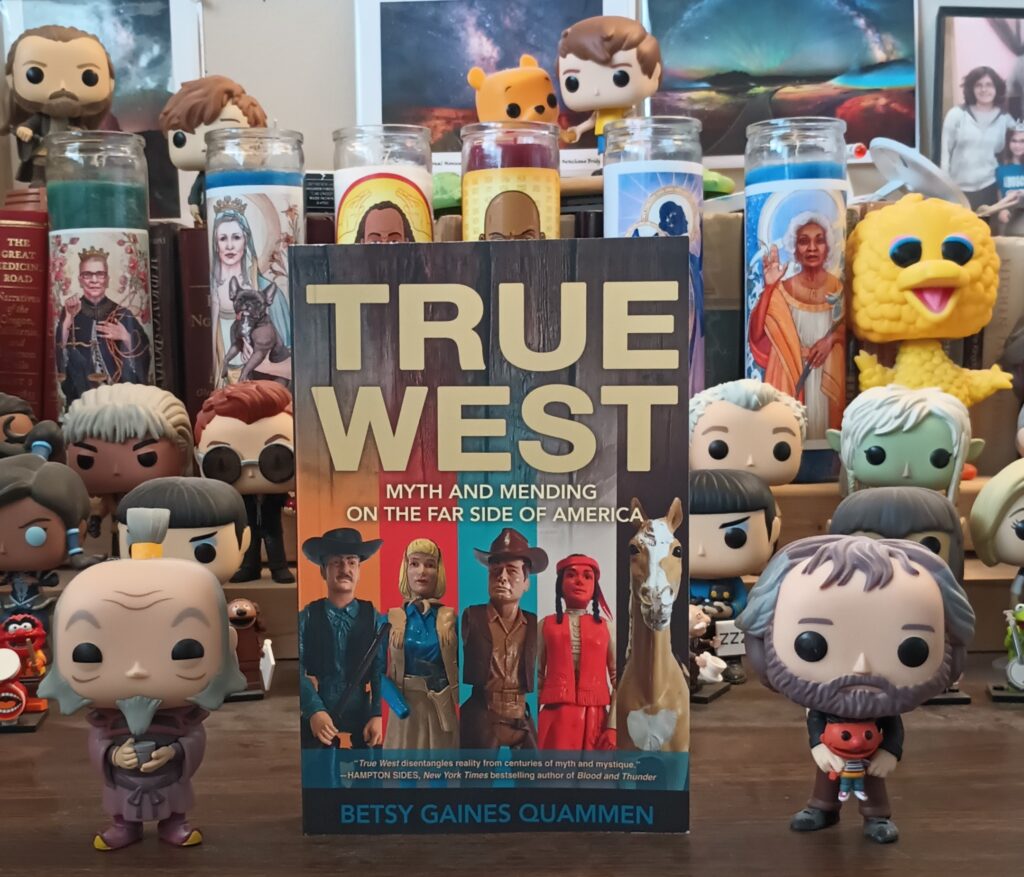

The cover of the book is wonderful: five of Quammen’s childhood dolls—a sheriff, a cowboy, a Native American woman, a ranch wife, and a horse. Each of them is damaged in some way—minus a hand, garishly colored or faded, armless. They’re symbolic of her argument. All together, they say: these myths? They’re part of the history of the West, its allure, its culture, and its appeal. But inside the book, Quammen insists that those who live in the West, do their work here, value its resources and opportunities, do not subscribe to them. Human values of honor, live-and-let-live, communication, and negotiation will sustain the true West as they do everywhere. The real West, true West, is more alive, more inclusive, more deserving of diligent, intelligent care than any vigilante, isolationist, or divisive individual or group—any collector of myths—might believe they have the right to suggest.