Review

———-

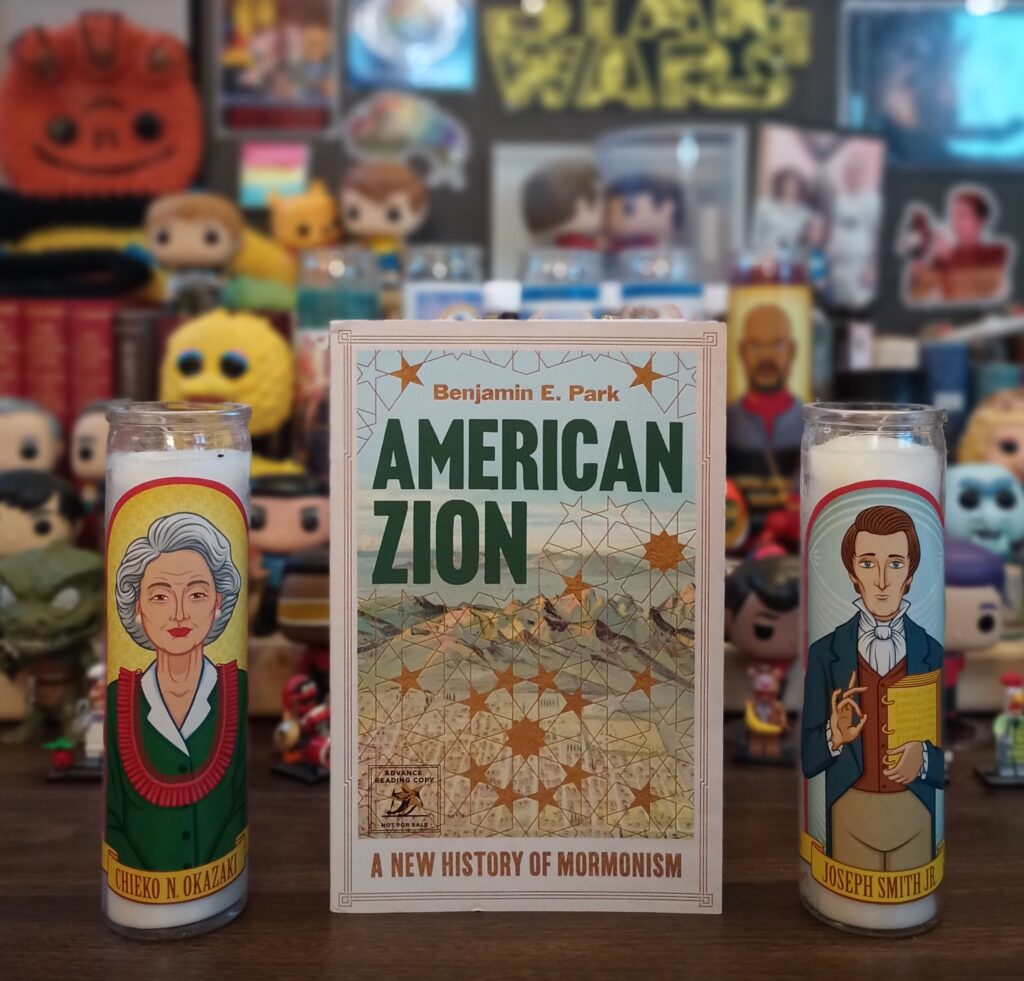

Title: American Zion: A New History of Mormonism

Author: Benjamin E. Park

Publisher: Liverlight

Genre: Religious non-fiction

Year Published: 2024

Number of Pages: xix-478

Format: Paperback

ISBN: 9781631498657

Price: $35

Reviewed by Sam Mitchell for the Association of Mormon Letters

Benjamin Park’s latest volume on Mormonism, American Zion: A New History of Mormonism, is a well-written and engaging history of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. An important entry in Mormon studies and Latter-day Saint history, American Zion will generate buzz and understanding for a long time to come. I am happy to recommend it both to insiders and outsiders of what some consider to be America’s largest, “homegrown” religious movement.

American Zion is divided into 10 chapters, along with a Prologue and an Epilogue. Each chapter details a period of the Church’s history, each chapter usually spanning 20 to 30 years and several dozen pages. Beginning in 1775 with the story of Joseph Smith Jr.’s parents and ending with details of Latter-day Saint life in 2023, American Zion has an ambitious project: to tell the story of Mormonism, from beginning to present. In general, it focuses on the life of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, though at times it addresses the history and practices of other sects that claim Smith as their founding prophet. These sects include what is now called the Community of Christ (formerly RLDS), as well as fundamentalist groups that split from the larger Church in order to continue practicing polygamy.

Of necessity, many events, ideas, and persons of the broader Latter-Day Saint movement, and of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in particular, are only briefly mentioned. It will be natural for some to read American Zion and exclaim, “But what about Event X, Person Y, and/or Doctrine Z?!” However, due to its sheer scope, Park has had to select those details that can help both insiders and outsiders engage with the Church’s story. Park treats his subject matter not reverently but respectfully (he explicitly notes that this is not devotional literature). As the title implies, Park is most interested in the interactions of the Church and the broader American religious, social, academic, and political milieu. Indeed, Park argues that one can understand the history of these aspects of American life by viewing them through the lens of Mormonism.

Throughout American Zion, Park focuses on female characters—especially Amy Brown Lyman—and their role within the Church, as well as the growth and historical foci of the Relief Society. He strives to center the stories of women in all periods of Church history. Park also devotes many portions of his work to issues of race (particularly regarding the priesthood restrictions that ended in 1978) and, especially in the latter half of American Zion, gender and sexuality.

Second only to Park’s focus on the intersections of Mormonism and America, however, is his interest in the intersections of Mormonism and academia. The history of Mormon intellectualism is a prevalent part of the book. Such a history is a needed one and is succinctly summarized in American Zion. It seems quite likely that as more and more Latter-day Saints find themselves drawn to academia, the need to understand their own intellectual heritage and forerunners will only grow and grow.

Part of the brilliance of American Zion is how well it reads like a novel—it is clear which characters are the protagonists and which characters and/or ideas have been divisive over time. Other historical figures are treated when necessary. This helps avoid flooding the reader with an overabundance of names, events, places, ideas, and teachings that will become less relevant by the time one reaches the next chapter.

Because of its narratological structuring, I would guess that in the coming days, comparisons between American Zion and Saints—the Church’s latest approach to telling its own story—will abound. Such reflections will likely increase and become more prevalent once the fourth and final volume of Saints is released. After all, the majority of Latter-day Saints have a superseding and near-constant interest in pre-and early Utah eras of their history and theology. Events following the arrival of the Saints in the Salt Lake Valley are often less remembered in members’ collective memory—perhaps the Raid, the Manifesto(s) on polygamy, the establishment of the Welfare Program, and certainly the 1978 revelation on priesthood are exceptions, but in general, these are isolated recollections. American Zion ties these and other aspects of Latter-day Saint history together all the way to the present. The third and upcoming fourth volumes of Saints do likewise, though obviously from a devotional perspective. As public recognition of Church history grows, the comparisons between these two retellings of the Latter-day Saint story will as well.

In conclusion, American Zion is an engaging read that does not shy away from difficulties or controversies. Of necessity, it omits a number of figures and events but does so to help its audience comprehend the broad outlines of Latter-day Saint history. For the amount of ground it covers, American Zion does a remarkable job at maintaining narrative cohesion and at helping readers follow the story of the Church from its beginning to the present.