Review

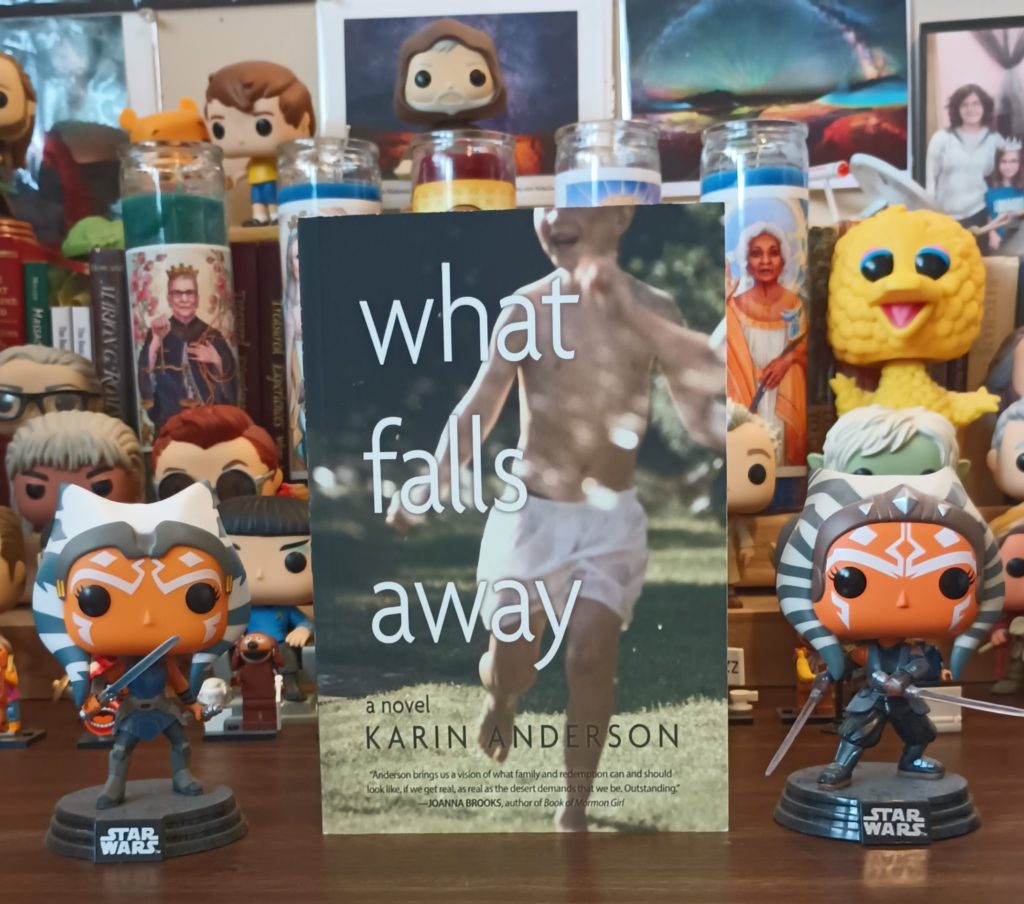

Title: What Falls Away

Author: Karin Anderson

Publisher: Torrey House Press

Genre: Novel

Year Published: 2023

Number of Pages: 373

Format: Paperback

ISBN: 978-1-948814-79-9

Price: $18.95

Reviewed by Julie J. Nichols for the Association of Mormon Letters

When I finished What Falls Away there were tears in my eyes.

I probably need to say that more carefully. When I finished reading this book for the first time, I nearly wept; and the second time, too. The final scene bursts the reader’s heart wide open. It both resolves everything (but really only a little) and exemplifies what every reader of many books (not just this one) knows: good books change us. The point of a good story isn’t resolution; it’s transformation. A good book makes us into new people, wider-brained and deeper-hearted. What Falls Away is a very good book.

Torrey House Press, says the “about” page inside the back cover, creates “conversations about issues that concern the American West,” conversations “at the cutting edge of social change,” “[reshaping] the dialogue on environmental justice and stewardship…by elevating literary excellence from diverse voices” (374). What Falls Away is Anderson’s second book to be published by THP because her themes—the aesthetically powerful influence of mothers’ hearts on institutional failure in the subcommunities of the American West—directly corresponds to the publisher’s mission.

The story, like all good stories, is simple enough to summarize but complicated to parse. In 1978, sixteen-year-old Cassandra Soelberg becomes pregnant and is cast out by her practically (if not officially) fundamentalist, fanatical LDS family. In 2019 and 2020, she is called home by an authoritarian older brother to fictional Big Horn, Utah, to nurse her aged mother in the pall of dementia. Leaving a home much further east (she is single and can do the work she loves online), she returns as requested, where—though she fervently tries not to–she must face, resolve, and transform the demons of family, rejection, theft, and loss that have hounded her for forty years.

Too young at sixteen to defend herself from the extreme Mormon beliefs and practices that were imposed on 1978 Cassandra, she has spent the intervening years rebuilding: attending college funded by a grandmother who saw a broader world, then creating a life grounded in her “prodigious” gift for art—and in her longing for the child she was forced to give up. Now, encounters with the past are inevitable, as are encounters with the future. The father of her lost son is now the bishop of the ward her mother lives in (has lived in all her life). The valley is full of the evidence of his crimes. But this is not a detective story or a story of revenge. Far more affectingly, it’s a story of family relationships, blood, and spirit; of appallingly incestuous and inbred (therefore grotesque) beliefs and practices; and acts of rescue, offering grace and space to grow.

Readers acquainted with small-town Utah culture will recognize the stereotypes Anderson invokes here, vicious and abusive but rendered human through Cassandra’s eyes since she was raised here, irretrievably marked by biases which, in the worst cases, have since calcified. She has words now to counter their falseness. Anderson marks clearly the stark differences in diction between, on the one hand, Cassandra, her generous grandmother, and curious, caring friends, and, on the other, those who still see Cassandra as a sinner and threat.

In fact, I had many moments of frank disbelief that either group would really use the vocabulary and phrasing Anderson puts in their mouths. But one of Anderson’s many writerly strengths is that she loves language. She swims in it as fish swim in water. Her character Cassandra is a gifted artist who, as a teenager, hardly knows why or how she draws. As an adult, she makes her living by her fully trained and developed art. It would be euphemistic to say Anderson is a similarly gifted writer. Her images trip us, revealing what’s underneath, what was always there that we couldn’t see till she wrote it. The rhythms of her sentences carry us deeper into and beyond where the story seems at first to lie.

The effect is startling. It’s not just that Cassandra’s art is an element of grace in a novel where outcasts’ finding each other constitutes the most spacious forbearance. It’s that receiving what is—reaching out to embrace beautiful diverse reality in its complex mystery—lifts even the most wounded to a kind of salvation. It may not be the salvation that the bricked-in Mormons believe in. But when their walls fall away, when they crumble as they must, it’s the only salvation there is.

Read this book. It’ll change how you feel about family. And if you have thought, as I have, that the biases, judgments, and practices of extreme Mormon culture have nothing to do with you, What Falls Away will change how you experience salvation, too.