Review

———

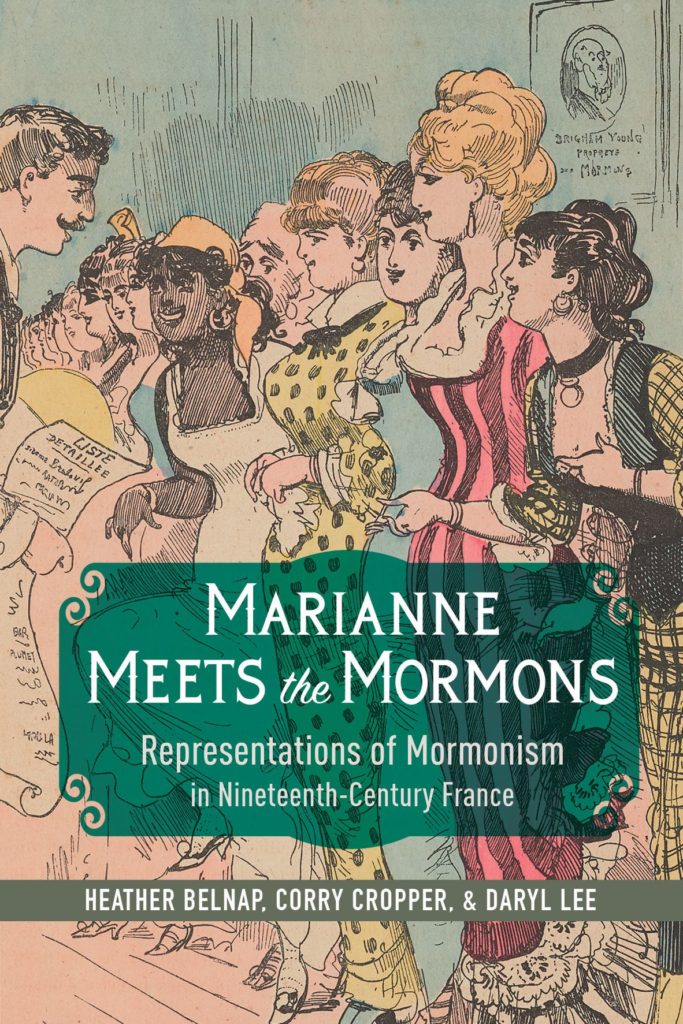

Title: Marianne Meets the Mormons—Representations of Mormonism in Nineteenth-Century France.

Author: Heather Belnap, Corry Cropper & Daryl Lee.

Publisher: University of Illinois Press

Genre: History

Year Published: 2022

Number of Pages xii + 304

Binding: Paper or Cloth

ISBN: 13-978-0-252-08676-2.

Price: $30.00 (Paperback).

Reviewed by Sam Mitchell for the Association for Mormon Letters

The premise of Marianne Meets the Mormons is clearly and evocatively stated by its authors: “Throughout the nineteenth century, Mormonism was used in France to expose, parallel, and parody contemporary French issues” (5). Marianne is not a history of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in nineteenth-century France, nor does it include rebuttals by early Mormons to their recast selves in the French imagination. Marianne centers not on Latter-day Saints but on the perceptions and portrayals of Latter-day Saints by a spectrum of French thinkers from the mid-1800s to the early 1900s. As is convincingly demonstrated by its authors, Marianne shows that “[nineteenth-century] French fascination with Mormons equated to holding a hypothetical mirror to French society rather than objectively understanding an external object” (9).

The divisions of Marianne are fairly logical and follow a somewhat historical trajectory, with obvious transgressions about which the authors are very straightforward (cf. 25).[1] The first chapter serves as an introduction to the entire work (1–25), while Chapter 2 examines the French understanding of Mormon communitarianism and utopianism in congruence and contradistinction with various French utopian efforts (26–52). The third, fifth, and sixth chapters deal with changing French attitudes towards feminism, gender, sexuality, marriage, and divorce, all against a Mormon backdrop that often highlights (positively and negatively) the polygamy of the early Utah period (53–96; 133–172; 173–198). Chapter 4 examines the French perceptions of Mormonism with and against occultism, spiritualism, and mesmerism (97–132), and Chapter 6 does similar work with Mormonism and colonialism (including as well French perceptions of Jews and Muslims; 199–236). A closing chapter (237–241) states the significance of the volume’s work in today’s world, noting that “the cultural instrumentalization of Mormonism came by way of fashioning Mormons into stand-ins for French men and women, French couples and families, and French colonists. … [We] have explored how the preoccupations of a non-Mormon culture were mapped onto Mormonism” (241).

Marianne’s overall premise is to show that Latter-day Saints were utilized—in friendly and unfriendly ways—to act as mirrors on then-contemporary French social, political, and sexual norms. The authors accomplish this by listing and examining many instances where Mormons and Mormonism are featured in the French discourses of the day. Some of these examples are stronger and far more convincing than others, while some—if left to themselves—are not as compelling. These various cases were drawn from a plethora of media, including art, poetry, and prose literature, newspapers and editorials, and plays. The thorough and in-depth examination of these various forms is often but not always grouped by kind—there are some chapters where art is discussed more heavily than in others, and there are some chapters where the bulk of the examination is focused on critical textual readings. When discussing art, the authors would often include the sketch or painting in question along with other contemporary pieces that likely influenced the artist or were generally prevalent at the time—a helpful method of showing that French perceptions of Mormonism were ingrained in their contemporary milieu.

I was happy to find myself eager to learn more about several of these primary sources used in Marianne. For me, one of the most interesting was a novel written by Albert Robida in 1883 called Le Vingtième siècle, discussed in detail on pp. 144–151. This work imagines the future of 1950s England, where “Mormons have left North America to colonize England, with the intent of expanding their influence across the continent through France” (144). This futuristic society has women with “achieved career status and political representation on equal footing with men” (144). Females work in typically male-dominated professions and campaign for their (polygamous) husbands’ political careers. “The [British] House of Lords is now the House of (Mormon) Bishops, and the electoral system of the House of Commons is based entirely on polygamy … When the unmarried Philippe walks the streets alone on a Sunday, the Mormons arrest and throw him into Bachelor’s Prison, a hilarious invention of Robida’s that shows the absurd extremes of a society built on polygamy” (145). Reading the perceptions and portrayals of nineteenth-century Mormonism by Robida, all in an attempt to examine his own French society, nearly persuaded me to become a French social historian myself!

Overall, the authors’ objective to show “Mormonism as a mirror” is successful. Indeed, I finished reading Marianne convinced that yes, the use of Mormonism in nineteenth-century French thought was indeed more a revelation of the thinkers and less of the “thought-of.” Such an argument and conclusion are fascinating, and certainly applicable to the study of receptions of (and by) Latter-day Saints in different parts of the world and in different periods of time.

In short, Marianne Meets the Mormons is an interesting and convincing read. Its many examples, drawn from a variety of French art and literary forms, help solidify the authors’ argument that Mormonism was a mirror through which nineteenth-century French thinkers could review, reflect on, and seek to revise their own society. The book is centered on their thoughts and writings, rather than on those of the Latter-day Saints they portrayed. As such, it is a welcome addition to researchers interested in the work of global Mormon studies and in the decentering of traditional topics in favor of examining outsider perspectives.

[1] While a chronology is located at the beginning of the book, I, as a non-expert on all things French, had some difficulty remembering which period of French history corresponded to what dates and what happened in which era. In general, the authors helpfully provided the years of the different Empires and Republics of nineteenth-century France throughout the text, though in future editions, it may be beneficial to include a brief opening chapter reviewing relevant French history, politics, and social movements.