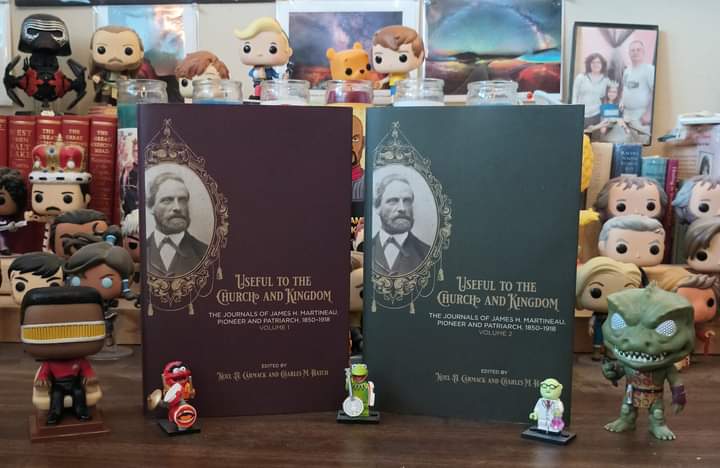

Title: Useful to the Church and Kingdom: The Journals of James H. Martineau, Pioneer and Patriarch, 1850–1918, Volumes 1 and 2.

Editors: Noel A. Carmack and Charles M. Hatch

Publisher: Signature Books

Genre: Documentary History

Year Published: 2023

Number of Pages: Volume 1: xlviii–598 (end material included); Volume 2: 601–1353 (end material included; pagination follows Volume 1).

Binding: Hardbound

ISBN: Volume 1: 978-1-56085-461-6 (hardcover); Volume 2: 978-1-56085-462-3 (hardcover).

Price: Volume 1: US $39.95 (hardcover); Volume 2: US $39.95 (hardcover).

Reviewed by Sam Mitchell for the Association for Mormon Letters

Though perhaps not as well-known as other early Latter-day Saint leaders and laity, James Henry Martineau is nonetheless an incredibly important resource for understanding early Utah Mormonism. A prolific journalist, Martineau’s accounts of daily life, religion, and landmark events in the American West provide scholars of all backgrounds a pivotal resource. The two volumes of Useful to the Church and Kingdom: The Journal of James H. Martineau, Pioneer, and Patriarch are a must-have on any researcher’s shelf.

These are not the first editions of Martineau’s journals. As the preface in Volume 1 indicates, “the Brigham Young University Press [published] the Martineau diary … in 2008 as An Uncommon Common Pioneer. Edited by Donald Godfrey and Rebecca S. Martineau McCarthy, that book met a pent-up demand by making much of the Martineau diary available.” The present volumes, however, are “extensively annotated,” with the preface’s author, Richard Francaviglia, arguing that Useful to the Church is now “the definitive version of the Martineau diary—a major primary and secondary source combined” (1:x–xi). The volumes’ editors, Noel A. Carmack and Charles M. Hatch, later add that the volume from BYU’s Religious Studies Center

while carefully transcribed and introduced—more ably served the family’s interests than wider scholarship. The volume … is an impressive by deficient work … [because it] fell short of offering a critical, historiographical analysis of his place among other laborious Mormon men of his stature, his life as a polygamous husband and father, and his skills as engineer and observant recordkeeper. (1:xlvi)

Regardless of how the reader may evaluate the differences between the 2008 edition and Useful to the Church’s volumes, Francaviglia correctly notes in his preface the latter’s extensive annotation, often on a broad array of subjects that are broached in Martineau’s writings. Many characters receive a full biographic entry in the volumes’ notes, which at times provides helpful information for the reader. One will notice that the majority of Useful to the Church’s footnotes deal with Martineau’s surveying, engineering, and mapmaking. This should come as no surprise, however, when one considers both Martineau’s professional endeavors as well as the expertise of the volumes’ editors (for instance: “Noel Carmack, an … authority on Martineau’s mapmaking”; 1:ix).

As noted in the volumes’ title, these journals cover Martineau’s life from 1850 to 1918, sometimes with daily entries by the diarist. However, it appears that Martineau would journal in “pocket diaries” and then later copy entries en masse into large journals:

“[We] must accept these journals as an emendation of Martineau’s daily, on-the-spot observations. The whereabouts of all but one of his pocket diaries are unknown so the journals stand as the representative—though emended—Martineau record. This in no way diminishes the importance of this record, but unfortunately we are left to wonder what he might have intentionally omitted for the sake of brevity or discretion” (1:xlii).

And omit Martineau did, as he himself notes:

“In this volume [i.e., the first of his compiled journals] are noted many things not worth record, while I find, on looking back, that I have omitted many that should have been noted. In part, this has been because some things appeared at the time of some importance, which time subsequently disproved; and some things, of apparently little moment afterwards proved to be important as time unfolded the future” (2:837).

The first of Useful to the Church’s volumes covers from 1850 to 1883, though in truth it actually begins at Martineau’s birth in 1828. Martineau spends the first pages of his journal to recount his family and personal history (cf. 1:3–24). That Martineau also journaled prior to his 1851 conversion to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is evidenced by a statement he makes while recounting his journey to go to the California gold fields, “I kept a journal, and had in it many sketches which I made, but before reaching Salt Lake City, some one stole it” (1:22). Throughout his journals, Martineau keeps meticulous detail of numerous events, and also records poetry that he writes while traveling or for specific individuals. Though there is more poetry in Volume 1, both volumes include interesting rhymes that reflect Martineau’s sensibilities and sense of self, Mormonism, and the world around him. A particular favorite of mine is found in 1:316–317, where Martineau writes “To My Priestly Robes,” a six-stanza poem describing the beauty and role of priesthood clothing in the Resurrection.

The second volume of Useful to the Church covers from 1883 to 1918, the year that Martineau’s first wife, Susan Ellen, passed away (2:1260–1263). Martineau himself died in 1921 (see 2:1263, n. 40). At the conclusion of Volume 2, two appendices detail Martineau’s 1854 encounter with John C. Fremont (2:1265–1271) and a 1907 letter Martineau wrote describing the Mountain Meadows Massacre (2:1273–1280). A “Family Pedigree” (2:1281) is also included. Both volumes end with a section of “Photographs and Illustrations,” including drawings Martineau included in his journals (1:585–598 and 2:1283–1292). These sections would have been more useful, I feel if at the very least Martineau’s illustrations had been included in the main body of the journals’ text, instead of being sequestered at the end of each volume. After all, Martineau refers in his journals to his drawings on multiple occasions. This method would have also allowed for Useful to the Church to resemble even more closely the physical layout and content of the volumes’ primary sources. This critique aside, the “Photographs and Illustrations” are helpful resources for contextualizing the volumes’ material.

Prior to Martineau’s conversion to the Church, he had been a religious man, but after his baptism, he became a man of his religion. While the volumes’ editors rightly focus much of their footnoted annotations on his career, one must also remember that Martineau considered himself first and foremost a Mormon. Pages upon pages of Useful to the Church detail Martineau’s life as he saw it—through the lens of the Church, its leaders and ordinances, and his role to all of the above. Oftentimes Martineau recounts the numbers and names of proxy temple ordinances and family histories, and almost every single patriarchal blessing he or a relative receives is recorded as well. Martineau writes to Presidents Brigham Young and Joseph F. Smith to request permission to move, and he serves as a clerk, counselor, and later an explorer for the Mormon Mexican colonies. When the Logan Temple was first dedicated, Martineau spent nearly every day for at least three months inside its walls performing ordinances for deceased relatives (see 2:616–627).

The sheer amount of detail that Martineau includes regarding his “day job,” including routes traveled, ranges traversed, and tools utilized, is staggering, to say the least. However, being interested in the development of the early Utah Church, its adherents’ lived religion, and Mormon history and theological praxis in general, I was drawn more to those such aspects of Martineau’s writing. These include, inter alia: temple ordinances; family history; the Mormon Reformation of 1856–57 (perhaps my favorite quote from this era is spoken by Elder Lorenzo Snow and recorded by Martineau: “The spirit of God influences a man to kick a-es”; 1:121); the United Order; rebaptism; healings (both by women and men); patriarchal and other blessings; polygamy; and the Mountain Meadows Massacre. While he was not an eyewitness of the Mountain Meadows Massacre, Martineau strives to provide an indefatigable defense of William H. Dame, a man he believes to be innocent of any wrongdoing during the tragedy.[1]

Though the editors thoroughly indicate mentions of the Massacre, and though Martineau himself writes about it on more than one occasion, there are other areas of early Utah Mormonism that are given more attention throughout Martineau’s record. His practice of polygamy is a major focus of the journals and often forefront in Martineau’s mind. Polygamy for Martineau includes not only marriages between a living man and living women but also between a living man and deceased women (he receives dozens of such sealings). One senses the love Martineau had for “the principle” when he in 1910 recounts an 1875 experience with the then-governor of Utah, a non-Mormon named Samuel Axtell:

“I saw he was a man of profound thought. He had unwittingly given a powerful, philosophic testimony in favor of the Law of plural marriage. … Gov. Axtell was all unknown to himself, a natural born Mormon, a man of true integrity” (2:1219–1220). An entry from December 1907 shows Martineau, by this point, a patriarch in the Church, meeting with a visiting Church authority (one “H.H. Cummings Gen Supt. Church Schools”) and “[blessing] him, that his wife Barbara shall know the Law of Plural Marriage is true and from God.” (2:1195).

Martineau’s courtships and marriages are tender and almost giddy. In 1897, upon hearing of an estranged wife’s death (separated from him not by her own will but by her relatives), Martineau in eulogy offers a brief, nearly curt, but quite informative summary of this particular plural marriage, as well as his view on the matter as a whole:

I married [Jessie Helen Russell Anderson Grieve] at the time of the passage of the last and most stringent anti-polygamy law of Congress [i.e., 18 April 1887], considering that to be the best way to show where I stood, just as I married Susan J. Sherman in 1857 when the U.S. government was about to exterminate all polygamists by aid of the army.

When Jessie and I were sealed, each of us had to go to the endowment house alone, enter by a different gate, and at a different time of the night, so no one might suspect. With only two witnesses, and the person officiating concealed from our view that we might not know who it was, and by the light of a single candle, the ceremony was performed.

But I knew who sealed us, by the voice—that of Apostle F.D.R [Franklin D. Richards]. We left the building as we came—each going our ways alone in the darkness to our homes. (2:967–968)

One senses during Martineau’s early polygamous years, when he had two wives that lived in relative proximity to one another, that there were occasional strife and hierarchical disputes between the women. In general, however, Martineau does not dwell on the hardships of polygamy, but on its perceived fruits, including families and blessings from God for obedience.

Martineau often goes to patriarchs to receive blessings, almost always referring to such as patriarchal blessings. These are recorded frequently for Martineau and various family members throughout the volumes. One senses a shift (at least in Martineau’s thinking) about the role of patriarchal blessings when in 1859, as Patriarch Isaac Morley is blessing Martineau’s children, Morley “directed me to lay on hands with him, saying it is my privilege to bless my own posterity. He also told me to gather all my children together, at some time, and bless them” (1:217).

In later years, Martineau becomes a patriarch as well. On 16 November 1898, Martineau encounters Marriner W. Merrill, an apostle, and tells him:

that I had never desired any office in the church of authority and power to sit and rule or judge the Saints, but only one. He said you have desired power and authority to bless. I said yes. I had always desired the power to bless people. He said, ‘You ought to be a Patriarch. [President] Woodruff told me to search for just such men as you and ordain them Patriarchs. But it must be done in order. Write to President Snow, tell him your desire, and tell him I consider you worthy, and that I would take great pleasure in ordaining you to that office.’ … I had previously (a few days) been told by the Spirit I would be ordained a Patriarch very soon. And now I prayed, to know if I had done right in the matter. I received a plain answer, in words, by the Holy Spirit, that I had done exactly right and had been led by the Holy Spirit. That I had been held in reserve, and gathered out from all my numerous connections for this very purpose, to take the lead in their redemption; That I had been ordained a Patriarch before I came to this Earth, and that all was according to the will of the Father. (2:994–995)

Martineau understood the office of Patriarch to include an authority to seal blessings (including but not limited to ratifying the seal of temple ordinances) as well as a power to heal the sick. In his later years, Martineau has a list of “regulars” whom he visits and heals. These occurrences, as well as visions, dreams, and folk magic (all noted in the volumes), contribute to Martineau’s own lived religion and to the lived religion of early Utah in general.

Useful to the Church is an incredible resource, and one that should not go overlooked by any avid researcher, historian, or student of the early Utah period of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. I am happy to recommend that it be found on your shelf and that it be perused often as you walk with Martineau through the dusty days of yesteryear.

[1] Compare these defenses with recent and strong arguments implicating Dame in Richard E. Turley, Jr., and Barbara Jones Brown, Vengeance is Mine: The Mountain Meadows Massacre and Its Aftermath. (New York City: Oxford University Press, 2023).