REVIEW

Title: Battlefields to Temple Grounds: Latter-day Saints in Guam and Micronesia

Editors: R. Devan Jensen and Rosalind Meno Ram

Publisher: BYU Religious Studies Center, Jonathan Nāpela Center for Hawaiian and Pacific Islands Studies, and Deseret Book

Genre: Religious History

Year Published: 2023

Number of Pages: 320

Binding: Trade Paperback

ISBN: 9781950304363

Price: $24.99

Reviewed by Mel Johnson for the Association for Mormon Letters

Since the 1840s, the leadership and members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (CoJC), even with its global missionary program, has been centered with a focus on the North American Great Basin westward to California. Inevitably, the history and biography about the CoJC and its members have emphasized mostly the seminal events of the great move and the colonization of Utah Territory and adjacent regions. However, the missionary outreach to the world has shouldered its way into the literature of culture, history, and politics of members far and away from “Zion” at home. A reader’s copy of Battlefields to Temple Grounds: Latter-day Saints in Guam and Micronesia (Religious Studies Center at Brigham Young University, March 2023) arrived and has been a thoroughly entertaining and worthwhile read. Battlefields to Temple Grounds may result in being the best such endeavor as well as a primer so far for a history of the CoJC mission fields. The studies of scholars led by R. Devan Jensen and Rosalind Meno Ram chronicle the Church’s entry and development of the CoJC into Micronesia in the vastness of the Pacific.

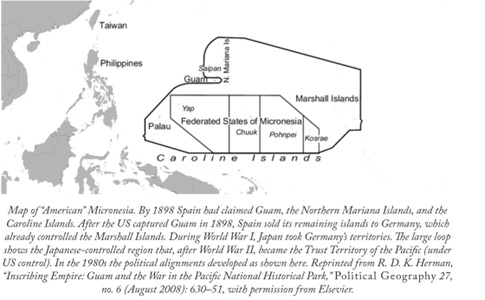

Battlefields to Temple Grounds generates a unique record of the native cultures of Micronesian intersections with the colonial imperialism of the nations of Europe, Asia, and the United States. The extensive narrative extends from Magellan’s landing in the early 16th century. The major emphasis explores and explains the coming of members of The CoJC to Micronesia in Pacific battles of World War II and develops its presence and growth of the Church to the present day in Kiribati, the Marshall Islands, Saipan, Guam, Truk (Chuuk), Pohnpei, Palau, Yap, and many other islands.[1]

I am going to include the main table of contents because its importance will promptly capture the layout and grasp the material it covers:

Micronesia Matters: An Introduction to Cultures, Colonization, and Christianity

by R. Devan Jensen and Rosalind Meno Ram

The Pacific War and the Rise of the Church in Guam and Micronesia

by R. Devan Jensen and Paul A. Hoffman

KIRIBATI AND THE MARSHALL ISLANDS

“He Remembers Us”: History of the Church in Kiribati

by Casey Paul Griffiths, Iotua Tune, and Eric Tonini

The Church in the Marshall Islands: A Cultural History

by Phillip H. McArthur

FEDERATED STATES OF MICRONESIA

The Church of Jesus Christ in Kosrae

by Daniel O. McClellan

Pioneers in Pohnpei

by R. Devan Jensen

The Church in Chuuk

by R. Devan Jensen, Rosalind Meno Ram, and Herryann Anepo Hinton

Cultural Differences and Converts in Yap

by Rosalind Meno Ram and R. Devan Jensen

REPUBLIC OF PALAU

Pioneers of Palau

by Clinton D. Christensen and Vonda A. Skousen

COMMONWEALTH OF THE NORTHERN MARIANA ISLANDS

The Saints in the Northern Marianas (Saipan, Tinian, and Rota)

by Karen Benson

MISSIONS, STAKES, AND TEMPLES

Micronesia Guam Mission and First Stake in Kiribati, 1980–2000

by Devan Jensen

First Stakes in Guam and the Marshall Islands, 2000–2011

by Devan Jensen

Steps toward Temples, 2011–2022

by R. Devan Jensen

The Yigo Guam Temple

by Po Nien (Felipe) Chou

Reflections on the Church in Guam and Micronesia

by R. Devan Jensen and Rosalind Meno Ram

The missionaries of the Latter-day Saints came very late to Micronesia in the 1960s. Protestant and Catholic missionaries came much earlier. As sea currents intermingle as they roll across the ocean, strong waves of colonial cultures, Christian and non-Christian, vigorously challenged and interacted with the indigenous cultures. European, Asian, and American nations variously claimed or colonized the islands and peoples, exerting influence in politics, education, and the economy, treating the islands and inhabitants as strategic bases or resources. The imperialists influenced the political affairs and policies, the instruction of the indigenous peoples, and the economic development of the islands, using them as military bases in the Great Game of global conquest for strategic position and resource extraction. The indigenous people have reacted to each wave and adapted, intermingling civilizations and cultures. After Japan’s bombings of Hawaii and occupation of Guam, and Wake Island, Latter-day Saint military personnel would enter Micronesia on the momentum of the American war effort. In the 1960s, CoJC missionaries began teaching military personnel and islanders, leading to the creation of the Micronesia Guam Mission and the Marshall Islands Majuro Mission, which includes Kiribati. And on these Pacific battlefields have developed peaceful temple grounds.

Let me make a quick comment on the writing and use of cartography in the book. I have noticed how effortlessly the editors and several writers negotiated the hard edges and explicit meanings that so often dominate most of the joint collegial professional writing, exponentially so when three or more academics share the written space. Such is not the case here. These writers capture in their joint work a sense of place, of people, and of culture, an effort that can be hard for one person much less more than a dozen in this case.

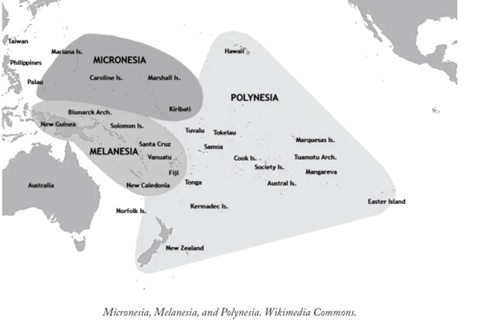

Also, the creation and use of maps to describe the geography as large as the continental United States of the native peoples’ homelands and the Pacific War’s battlegrounds complement the expert writing. Their construction demonstrates by cartography how Land and Ocean make the human. The maps below witness the vastness of Micronesia and its relationship to Polynesia and Melanesia. (4, 5)

The reader will enjoy the arrangement and chronological approach to the themes and challenges as they are explicitly identified and explored (2):

- What are the island groups and cultures of Micronesia?

- What are the major waves of colonization?

- How did colonizers affect the various cultures of Micronesia?

- How did Christianity affect the Indigenous cultures of Micronesia? •

- How did the Pacific War introduce Latter-day Saints to Micronesia?

- What challenges did Micronesians face during and after the war?

- How have indigenous members adapted to Church culture and teachings?

- What have missionaries learned from the indigenous cultures?

- What do Micronesian Saints think about the Yigo Guam Temple and the forthcoming Tarawa Kiribati Temple?

I appreciated how the writers developed a maturity of Voice that strengthens and enrichens the unity and continuity of the book’s themes. The first example is that of Marina and Ronnie Oei, who:

were originally from New Guinea and of Indonesian ancestry but had raised most of their family in the Netherlands. A little while after her first dream, Marina received another important message in the night. I saw two men ring our doorbell. As I opened the door, I saw two young men standing wearing blue suits and white shirts with a name tag. I heard a voice say, “Do not close your door, but let them in and listen to what they have to say to you.” The next day, I and my husband went to visit his niece. When we came home my son Richard said someone called and asked, “Is this the Oei family?” My son said, “Yes, but my parents aren’t home.” So the person told my son that they would come the next day at 11 a.m. My son said the person spoke English, so I prepared a meal for them and waited that Saturday. When someone rang our doorbell, I opened the door and saw two young men; one of them looked like the one I saw. (186)

The inclusion of indigenous voices endows authentic history.

And I also appreciated the thematic continuity of missionary work of the various Christian denominations:

Latter-day Saint proselytizing in Micronesia is deeply enmeshed in the history of colonization that preceded it,” writes Phillip McArthur. “The missionaries rode in on the coattails of American imperialism that both facilitated their entrance and provided the background for their initial teaching efforts.” Telling the story of religious proselytizing in Micronesia requires doing so within “indigenous frameworks of understanding and practice,” he adds. As authors, we highly value the voices of Micronesians and have done our best to share the stories of those who joined The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Micronesia and either remained there or are part of the Micronesian diaspora. Many stories are first-person accounts of the development of the Church in Guam and Micronesia. Contributors also reflect significant experience in the Pacific and multiple nonindigenous perspectives: American, Asian, European, Jesuit, and Latter-day Saint (including members and missionaries). For example, we interviewed Father Francis X. Hezel, a Jesuit priest who is a foremost authority on Micronesia. (2-3)

The cross-cultural misunderstandings pertaining to differing peoples quickly became apparent. Additionally, how the missionaries understood the indigenous peoples in the convert field was important. Did they think of them as uneducated or backward or unequal, as was the case with North American indigenous peoples? Were the missionaries complicit in thinking so? Did the converts adopt submissive attitudes to church leaders while conveying an attitude of superiority toward their own familial and kin groups and neighbors? I remember the numerous missionary reports to our wards when I was young in which they told the audience in kindly yet patronizing tones how they (the missionaries) had come to love “those people” and how they brought enlightenment of the gospel to them.

The professional and serious layperson interested in missionary work involving disjointed cultures separated by vast seas and skin color and language and understanding of their world should buy Jensen and Ram’s work. The Micronesians speak a dozen different dialects and many use English as a second tongue (6). The research is impeccable and gives great insight into a great work to overcome cultural differences and misunderstandings, not the least being the nuance of language.[2] The writers counsel:

Mission leaders and missionaries tried to master many languages and integrate Church practices into existing cultural communities on each island. Calling and mentoring indigenous leaders and seminary teachers were important to the growth of the Church on each island. Mission leaders who tended to find lasting success in retaining converts found a balance between strict calls to obedience to Church protocols and kind and gentle nurturing and mentoring of indigenous leaders. If we were to offer advice to missionaries serving in Micronesia, we would emphasize learning the language and culture and nurturing with kindness—teaching practical skills while emulating Christian virtues. We would also suggest focusing on learning from local members as much as seeking to teach them. (294)

Materials primary as well as secondary well source Battlefields to Temple Grounds, much of it based on the personal experiences of missionaries as well as members in Micronesia.

The book is timely and worthy and demands that it should attract a large readership. I have no doubt that those who read it will recommend it to others. It teaches lessons in having to surmount societal chasms of misunderstanding in language as well as cultural and racial prejudices. The work uniquely directs the reader to inspect one’s own personality and relationship with Christ when in contact and conflict with the “other.” It becomes a measure of the reader’s personality.

The book may well begin a young missionary’s search on how to succeed in differing cultures. Having listened to many returned missionary reports, I finally have had to accept that a Mormon savior complex, although well-meaning, is a real thing. The book can instruct how to deal with the fact that s/he is the “other” in the mission field, not the local inhabitants. The world’s intrinsic values in regional cultures inevitably move and motivate the community’s inhabitants’ social and cultural pathways. The quicker the young missionary (or senior service missionary, for that matter) can adopt and exhibit an inclusive viewpoint, the experience will become richly rewarding.

You want Battlefields to Temple Grounds on your shelf at home and in the office. Not only will it impress others, but you will also have it handy when those questions come. The Religious Studies Center has a digital version coming. I want it on my Kindle, which is either in my pocket or on the nightstand next to my bed for when those niggling questions come in the night; and they will.

[1] Ironically, my father (Army) and stepfather (Marines) participated in the Mariana Campaigns at Guam and Saipan, respectively. They would later be converted to the CoJC after the war. My father never stepped onto Guam, his invasion craft having been mortar shelled offshore, every man killed or wounded. He woke up in a hospital ship.

[2] My father believed that language separates people, that “people at the top of the mountain speak differently than those in the valley” by design, not accident.