Review

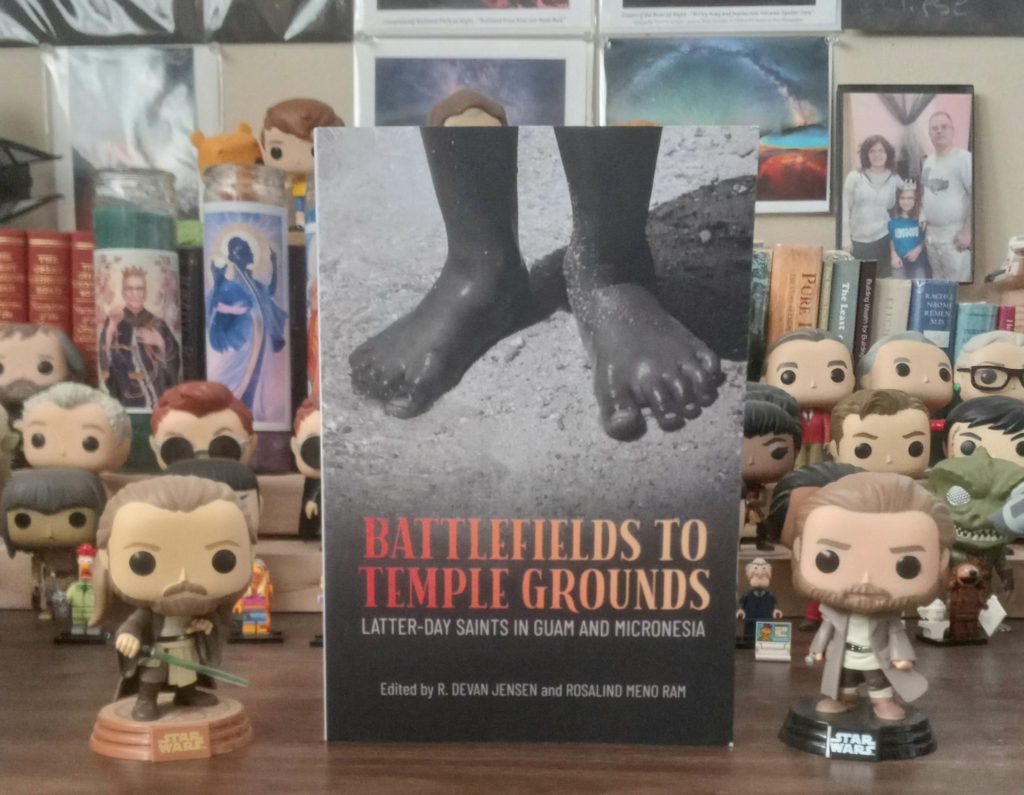

Title: Battlefields to Temple Grounds: Latter-day Saints in Guam and Micronesia

Editors: R. Devan Jensen and Rosalind Meno Ram, Editors

Publisher: Religious Studies Center, BYU, and Deseret Book

Genre: Religious History

Year Published: 2023

Number of Pages: 320

Binding: Trade Paperback

ISBN: 9781950304363

Price: $24.99

Reviewed by Kevin Folkman for the Association for Mormon Letters

In the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, with its emphasis on ministering, social interaction, and fellowship, it can be easy for members to have a limited worldview outside their circle of fellow members and family. A legacy of persecution and struggle for survival can also contribute to what may appear to outsiders as insularity. For decades, the same argument could be made about Church history research that focused on the story of the restoration, the trek west, settling Utah and surrounding areas, and biographies of 19th-century church leaders.

In recent decades, there has been a new interest in the church’s history in Latin America, Africa, and other areas outside the United States and Western Europe. In addition, more attention has been paid to cultural issues and political forces that have impacted the LDS Church and its members in recent decades. BYU’s Religious Studies Center has published a number of books relating to Church history from a worldwide perspective.

Battlefields to Temple Grounds, a compilation of research on the Church’s expansion in the Western Pacific, is one of those books. Edited by R. Devan Jensen and Rosalind Meno Ram, it explores the history of the Church in the remote islands encompassing Guam and Micronesia. While other Christian churches, mostly Catholic and some Protestants, had begun missionary work in these areas in the 19th century, it wasn’t until World War II that LDS members of the armed forces first encountered this culturally rich but extremely remote area of the world. Spread over an area larger than the continental Unites States and caught between political and cultural crosscurrents from both sides of the Pacific Ocean, the various island states of Micronesia represent a broad variety of languages, customs, and societal influences. During and after WW II government officials and service members who were LDS looked to Micronesia as a new and potentially fertile ground for missionary work.

But such work was not easy. The first missionaries to Guam arrived in the 1960s and a decade later for much of the rest of Micronesia. As Jensen, Ram, and their collaborators point out, each set of islands had their own languages, cultures, and customs, often differing widely even in a particular island chain or atoll. Missionary efforts were initially directed through the Hawaii Honolulu mission of the church, thousands of miles away, making support and communication difficult. The first missionaries had no formal training in the languages or education in the cultural norms of the areas. Housing was often difficult to come by.

One of the first exposures of the Church to Micronesia came through a request from a small school in Tarawa atoll in Kiribati, where the headmaster applied to a number of different organizations seeking supplies and other assistance. This came to the attention of Alton Wade, overseeing Church Education System activity in Hawaii and the Pacific. The headmaster, Waitea Abiuta, was trying to find secondary education for the students of his school, who rarely got more than a simple grade school experience. This led to a number of students attending the Church’s Liahona High School in Tonga, where the church was already established. Several of those first students joined the Church while attending there and brought their new faith back with them to their island homes. Eventually, the Church coordinated with Abiuta and established the Moroni High School on Tarawa, with Abiuta, now a church member, as the principal. This led to more formal associations with the Church and the arrival of missionaries.

While the early missionaries faced the traditional challenge of learning new languages, by far the greatest difficulty came through cultural misunderstandings. Some islanders were amused at the white shirt and tie dress standards of the missionaries, a challenge in a hot and humid climate, while others saw it as a sign of inequality between the missionaries and the people [p51]. There was also the problem of foreign missionaries viewing the indigenous islanders as simple or primitive, which at times led to patronizing attitudes, perceived by the locals as a new wave of colonialism [p76-77].

One perplexing obstacle facing the early missionaries came from a lack of understanding about the matrilineal (not matriarchal) nature of the society of the Marshall Islands. Used to patriarchal and male-led church leadership, missionaries faced unforeseen difficulties. Inheritances and family associations came through the women, who often were chiefs or clan leaders. Special deference was given to female family members. In one case, when it came time to set apart a woman as the district Relief Society president, the district president, a local member of the same clan, but not as high ranking as the sister, could not bring himself to lay his hands upon her head to set her apart, as touching such a high-ranking female was a serious social breach. The standoff was ended only when a senior missionary, a counselor in the mission presidency and thus not of her clan, set her apart [p86]. In addition, releasing someone from a position was viewed as a sign of disapproval by the church, as local customs associated rank and title as lifelong attributes. Such releases often confused and angered local members.

As one of the authors in this volume wrote:

On those occasions when the American missionaries and leaders disentangled their own culture from the core principles and practices of the Church, the integration proved inspiring and productive. On the other hand, when they have insisted upon their own cultural frameworks as concomitant with gospel teaching and Church governance, there has been slippage, misunderstanding, confusion, and sometimes resistance. [p74]

In their conclusion, the editors, who along with the contributors to this volume, all have firsthand experience in the area, reinforce the need for understanding such cultural cross-currents, something that applies not only to Micronesia but to other areas around the world:

If we were to offer advice to missionaries serving in Micronesia, we would emphasize learning the language and culture and nurturing with kindness —teaching practical skills while emulating Christian virtues. We would also suggest focusing on learning from local members as much as seeking to teach them. [p294]

Such cultural conflicts are lingering relics of the history of colonialism and exploitation that have plagued much of the world outside Europe and North America.

In the nation of Kiribati, approximately 20% of the population are now members of the LDS Church. Two temples are either completed or are under construction in the nations of Micronesia. Church growth is also mirrored in a greater awareness of these islands, still some of the most remote places on Earth. This reviewer recently discussed reading this book with local missionaries in Washington State, and both missionaries knew firsthand other missionaries who had either already served or were recently called to serve in some of these nations.

In Battlefields to Temple Grounds, the authors and editors have mined primary source material from the many men and women who have participated in the growth of the Church in the region. Volumes from BYU’s Religious Studies Center sometimes have limited printings and thus reach few people. Jensen and Ram’s contribution is one that deserves a wide audience for the insights and lessons it offers in overcoming cultural divides and paternalistic attitudes.