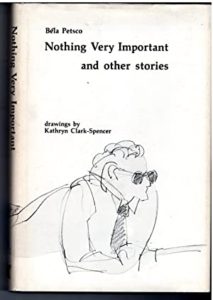

Nothing Very Important and Other Stories

Nothing Very Important and Other Stories

By Bela Petsco

Illustrated by Kathryn Clark-Spencer

Meservydale Publishing, 1979. Signature, 1984. Hardcover: 209 pages.

ISBN: 0-911712-60-7

1979 AML Award: Short Fiction

Reviewed by William Morris (12 March 2002)

I first came to know Bela Petsco through his silence. I don’t remember where. Some essay on Mormon literature, I believe, that mentioned that he hadn’t published any fiction since his groundbreaking collection of short stories. And shortly afterward his name was invoked on the AML-List where I was lurking at the time. His name was invoked in respect tinged with sadness and frustration. I don’t remember the thread topic or who (there were several) brought his name up, but I, hungry Mormon lit. novice that I was, imprinted it in my mind. And though his name came up again in my studies and discussions on the AML-List, what Petsco meant to Mormon literature remained hazy for me. The impression I carried was of a promising young writer gone silent, perhaps intimidated by the burden of expectation, possibly bowed by an unsympathetic Mormon audience. I’m sure it’s a false impression. And it feels strange to speak of him like this — especially to those who know him and his work from when it was freshly ripened. But I can’t cover the distance and treat his work as if it has just been published, so that has colored my reading and this review.

Nothing Very Important and other stories is a collection of 20 connected short stories punctuated by brief (a paragraph or two) bits of narration or description or dialogue. Most of the stories are narrated from the point of view of Elder Mihaly Agyar, an older convert born of Hungarian immigrants. But not all. The first story takes place shortly before his mission to Southern California and Arizona; the last two stories take place shortly after his return to his home in New York City.

Agyar is not a model missionary — he breaks mission rules. But only the ones he perceives as trifling. As an older missionary and recent convert, he finds the bureaucratic trappings of mission life amusing and frustrating. He remains conflicted about the emphasis on the number of baptisms and steadfastly credits other elders for “his” converts (the story “Numbers” deals directly with this conflict and also exposes readers most explicitly to Agyar’s thought processes — it’s a masterful work of Mormon discourse interiorized and in conflict). But throughout the stories he maintains a strong belief in the importance of the gospel and especially in connecting with and loving others.

What happens in these stories is sometimes relatively insignificant; sometimes it’s shockingly real. People, even missionaries, make mistakes and sin. The style is fairly sparse. Some of the stories are quite short. But things are said or done because of Agyar’s presence, because people — elders, members, investigators — open up to him. The flow of energy, of attraction and frustration and hope, is almost always towards him. He is a touchstone both for the reader and the people around him.

I’m not sure how to label it, but the flow of the stories feels to me like memories of a mission — a mission recalled. The connections between stories aren’t always clear. Certain moments, certain attractions remain, but they can’t all be tied together in a package and adorned with a prim bow. The short paragraphs between stories add to that effect. They often capture an archetypal moment or theme of mission life, a gesture or conversation or attitude. But the stories themselves create that feeling too, and, in the end, it’s obvious that the form of the collection is recreating Agyar’s own attitude towards his mission. All the events and places and people add up to “no form — no pattern” (207).

From Agyar’s homecoming talk: “A mission is neither all good — nor is it all bad. A mission is a mixture. It is something to be experienced” (191).

I am glad that I finally read Nothing Very Important and other stories. My mission experience was somewhat different, but my memories of it remain fragmented. Reading these stories was a resonant experience.

Perhaps it’s my peculiar critical view or the twenty intervening years of Mormon cultural history, but this collection seems naive. No. Simple is probably the better word. Maybe even innocent. What I mean is that the stories demand to be read as just that — stories. Trying to tie them into large ideological discussions and concerns is a futile, arrogant gesture. So I guess I’m defending Petsco’s silence even thought I know nothing about it. These stories deserve readers who will react to them on a personal level — readers who will cringe and cry, exult and mourn. Readers who will interact intensely with the text, yet at the end, not draw any conclusions or insist on interpretation, but will, with Agyar, shrug their shoulders and say that, well, it was nothing very important. I’m sure these readers existed in 1979. They do now. But there should be more. And they should be Mormon.

In short, this collection should be republished. With the surge of fictional mission narratives that have been published in the past five years, it’s time for this one to reappear. I don’t know if it would find a wide audience, but at least it could find the next generation of those Mormon readers who have similar reading sympathies as those who championed it when it first came out. I had to wait two months for my university library to order it from BYU. And I’d gladly pay for a used copy (including shipping) if anyone has an extra one.

Oakland, California 2002