Review

———

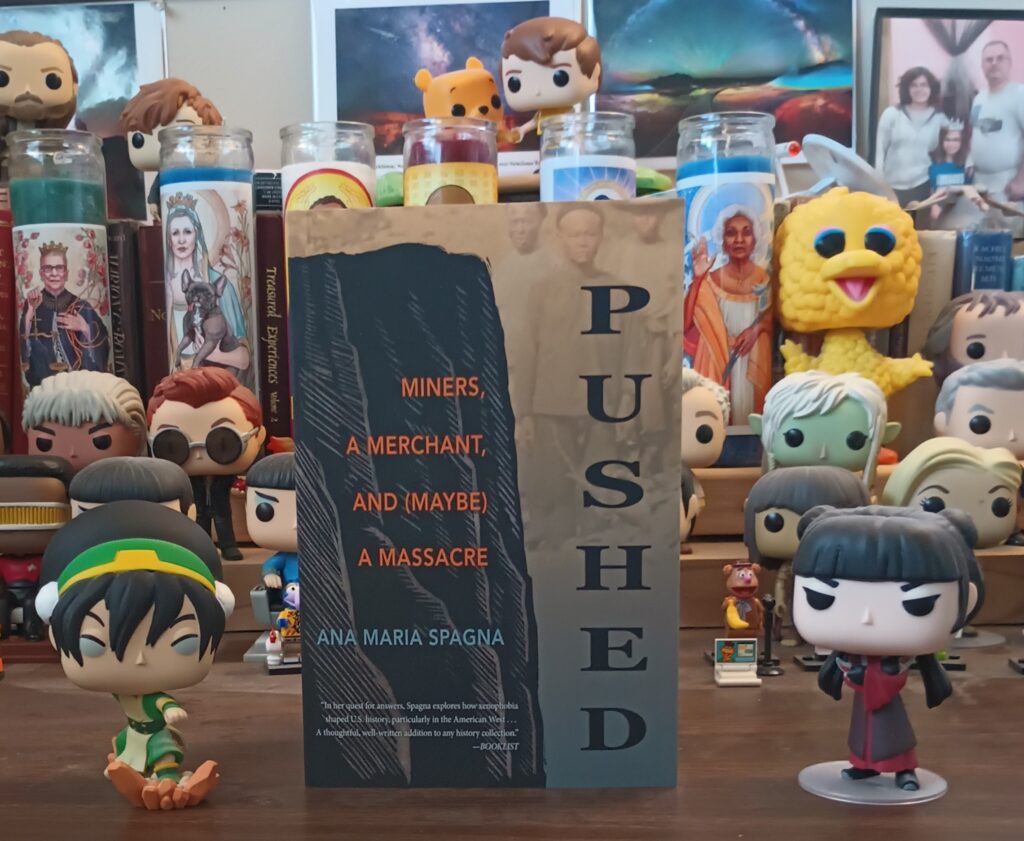

Title: Pushed: Miners, A Merchant, and (Maybe) a Massacre

Author: Ana Maria Spagna

Publisher: Torrey House Press

Date: 2023

Pages: 214

ISBN: 978-1-948814-69-0

Cost (paperback): $15.95

Reviewed for the Association for Mormon Letters by Julie J. Nichols

This is—to tell you upfront—a book about race and place. From the first sentence, Spagna’s voice is strong, trustworthy, and beautiful. These are the two first things to know about this book. Even if you’re not at first particularly interested in the ambivalent history of a small town in Washington State, the storytelling will get you hooked.

Every good book teaches its readers how to read it. Pushed’s prologue describes the physical-intellectual-emotional location of Spagna’s story: a former backcountry trails worker, she now lives in an isolated mountainous corner of Washington on Lake Chelan, where a history of the Indigenous peoples of the region caught her eye.

Why? Because a new tugging had begun. Simple questions that may be easy enough to answer in some places, but are murkier here: Who came before us? What did they do? Who and what did they love? How did they experience red heather ridges or too-long winter nights? (4)

As she reads on, she discovers a story she’s never heard: a fact? or a rumor? about an alleged massacre, a murder of an unverified number of Chinese miners off a bluff outside the town of Chelan in 1875, by Indigenous attackers. Or maybe White men dressed as Indians. (My ancestor Patrick Cragun disguised himself as an Indigenous person to throw tea off a ship in the Boston Harbor in 1773, so this version of the story didn’t seem too impossible to me.) Or maybe it didn’t happen at all. Three versions, three angles on a moment (or not) in the history of the place where Spagna lives.

Because it was 2016 and a new administration was pushing immigrants out of the United States, Spagna, chilled by the reality of xenophobia then and now, was moved to chase down the truth of its echoes in her own corner of the world, to prove it or disprove it if possible. This book is the story of the chase and its implications.

Each of the three versions gets its own section of the book. In each section, the individual version is imagined, its present-day advocates are interviewed, its scant documents unearthed, and its fragments pieced together. Readers meet Spagna’s interviewees, traveling with them to possible sites, invoking their visions of possible pasts.

She learns about a Chinese merchant, a successful community member whom she names variously Ah Chee and, later, Chee Saw—names she finds in newspaper articles and census reports but never specifically in connection with the supposed massacre. Was he a miner? Was he murdered with the other supposed miners? She can find no record of his (or any other Chinese men’s) deaths; in the third section she learns of the Chinese custom of sending the bones of deceased people home to China, but she can find no record of such shipments for any Chee Saw or miners.

Yet the story persists. Spagna carries her readers with her to various towns in the area, to libraries and museums, and to the homes of storytellers who have their own opinions about what might have happened and why. Contemporary characters like Dave and Sue Clouse, friends who’d heard of the massacre, knew as little as Spagna but were willing to search out possible sites of the alleged “push”; Arnie Marchaund, docent of the Depot Museum in Oroville and member of the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation, who grinned as he said his people had pushed the Chinese over the edge; and Dorothy Petry, who happily dowsed in the local cemetery for the possible graves of the Chinese—these and other twenty-first-century participants in the search weave in and out of Spagna’s story along with the long-dead characters who lived the nuances of the multi-layered past. Indigenous leaders, Whites who stood up for the reviled Chinese, neighbors who helped Chee Saw, and those who may have been his rivals—all make their appearance.

The stories are never blurry—I mean the reader never gets lost, as Spagna spins the possibilities of the various versions. Ultimately yes, the facts are blurry. But what blurs them is, paradoxically, skillfully made clear. People see what they want to see, believe what they want to believe, and isolate and exclude where they want to. The book is a paean to compassion and neighborliness, a quiet condemning of ways of thinking that might have culminated either in a massacre or in century-long rumormongering.

Spagna’s final section is both sobering and full of light. “People love their massacres,” she quotes someone as saying. It’s possible to believe there was no real massacre at Chelan Falls. “At the center of this story,” she says in a July 2023 interview with The Rumpus, “is a newspaper article that glamorized and sensationalized this supposed massacre. If anything is damning, in terms of what I’m trying to do, it’s the legacy of this writer in 1892.” (at https://therumpus.net/2023/07/27/ana-maria-spagna/)

The key to this eminently readable book is that powerful ambiguity: not that there was or wasn’t a massacre, but that there ARE massacres, that humans can think of them, perpetrate them, believe in them, perpetuate them. Let it stop: that’s Spagna’s final message. But the stories along the way have been informative, illuminating, clearly and beautifully told. Torrey House has done it again: fine writing, deep love of the earth and humanity, and better-than-excellent book production make an equation nobody can disprove.