Review

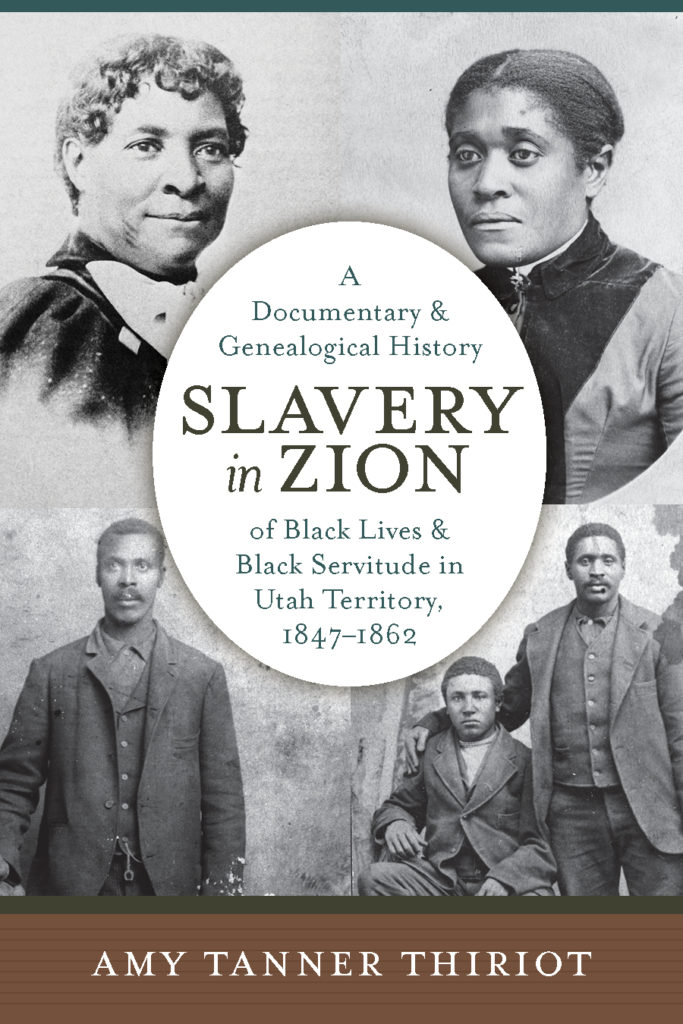

Title: Slavery in Zion: A documentary and genealogical history of black lives and black servitude in Utah territory, 1847-1862

Author: Amy Tanner Thiriot

Publisher: The University of Utah Press

Genre: History

Year Published: 2023

Number of Pages: 447

Binding: Hardcover or Paperback

ISBN-13: 978-1-64769-085-4

Price: $95.00 or $39.95

Reviewed by Dan Call for the Association for Mormon Letters

Many of us born in the previous century had our first memories of the pioneer narrative impressed upon us through flannel boards, artwork from church publications, occasional films, monuments, stories, history books (if you came of age in Utah), reenactments, even an obscure board game called “Zion.” Sadly, one common trait to all of these representations is that they uniformly centered on Whiteness, giving the impression that there was no ethnic diversity among the settlers in the Utah territory. Indigenous people were sometimes represented as Canaanites, about to be assimilated or swept aside. Another unfortunate outcome of this messaging was the notion that contemporary people of color in Utah were relative newcomers, yet to leave their mark on the state. What’s more, while I applaud relatively recent efforts to paint a more diverse picture of pioneer history, to my knowledge they continue to present a narrative of the Great Basin as a sanctuary of freedom, where settlers could shed the burdens which plagued them back east. Amy Tanner Thiriot’s Slavery in Zion: A Documentary & Genealogical History of Black Lives & Black Servitude in Utah Territory, 1847-1862 stands as a corrective to this narrative, documenting a historical facet many of us never suspected.

True to the title, Slavery in Zion documents the lives of roughly 100 Black individuals from this time period who came to live in the Utah territory. The decision to include the word Zion in the title led me to anticipate that this book would have a stronger focus on the part of the LDS church in perpetuating or enabling slavery and racial oppression within the borders of Utah. This theme, however, plays a secondary role as Thiriot’s main concern remains firmly centered on the lives and circumstances of the people who experienced enslavement in Utah. This does much to fulfill the stated goal in her poetic preface of honoring the West African concept of Sankofa: going back for that which was lost and trying to tell the history of people who have otherwise remained erased or silent for over 150 years. One of the memorable images included shows how Black Utahns were literally erased from a photo taken in front of a Relief Society building during this time period.

The first portion of this book is a straightforward history that mostly tracks developments according to regions from where Utah settlers originated. The second section is an encyclopedia of all the individuals for whom Thiriot could find historical documentation. I found myself jumping back and forth between the two sections, seeing how she pieced together a fuller picture from all the fragments amassed through her work. Enslaved Blacks who came to Utah found themselves navigating an emerging society held together by religious and economic preoccupations in an unfamiliar region, while the enslavers found themselves living alongside and sharing pews and scarce resources with outspoken abolitionists. Lawmakers passed legislation apparently aiming to mollify their community whose macrocosm was tearing itself apart back east. In all of this, we get intimate portraits of how these pressures affected the lives of individuals such as Biddy Mason, Samuel Bankhead, and Tom Church. For some, Utah was a relatively short stopping point before being driven further West or forced to go back east. While there were those who lived long enough to enjoy freedom as adults, others died tragically right before emancipation. I was equally engrossed in learning more about more well-known figures, such as Green Flake, as I was to learn about dozens of others who were completely unfamiliar to me. The account of the murder of Thomas Coleman, for instance, is made all the more horrific by the indifference of the justice system.

The closer I got to finishing Slavery in Zion, I found myself becoming more emotional. I longed to hear more directly from these people, to read their words and learn what they were really thinking about their world, their neighbors, the laws, the church, their beliefs, their families, and what it meant to them to be Black. We may never know the answers to these questions, but now that we have access to their names and know some of their circumstances, we can ensure that they are never again left out of the story. The thrill of at last seeing this facet of Utah history getting its long overdue attention also renews my hope that other suppressed narratives will soon see the light of day.