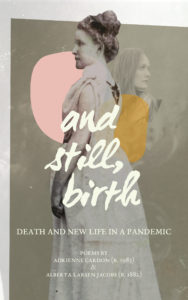

Adrienne Cardon introduces And Still, Birth: Death and New Life in a Pandemic, a poetry chapbook she wrote in collaboration with her great-grandmother, Alberta Larsen Jacobs, and her 100-year old poems. Published by the Center for Latter-day Saint Arts.

Adrienne Cardon introduces And Still, Birth: Death and New Life in a Pandemic, a poetry chapbook she wrote in collaboration with her great-grandmother, Alberta Larsen Jacobs, and her 100-year old poems. Published by the Center for Latter-day Saint Arts.

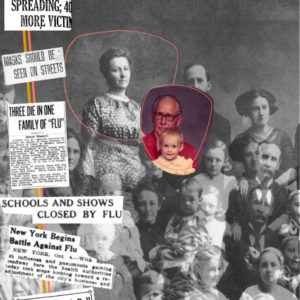

China became a viral tinderbox in January, 2020, right around the same time I hit my third trimester. I was a bundle of nerves carrying a bundle of joy. Soon after, my mother phoned to tell me not to worry. After all, my grandfather was born during a pandemic. He was kept in a cardboard box on the oven door of a wood-burning stove to keep him warm, apparently in the hopes of providing some protection from the 1918 Flu.

Not to even pause here to consider how our ideas about infant safety have changed over the last 100 years (cardboard + baby + lit stove = kaboom?), I was meant to be comforted by the knowledge my great-grandmother had endured a pandemic pregnancy. And I did find some strange solace in knowing this. (When I went into labor with my first child, my mother delivered a similar pep talk tale of my great-great grandmother Zina D.H. Young, who gave birth to her son on the muddy banks of the Chariton River, in a covered wagon, during a rainstorm.)

If my ancestral mothers could labor in such unfriendly and perilous circumstances, who was I to complain? What was a little coronavirus compared to the knowledge that I was descended from the labor gods?

Turns out, it was worse than we expected. (And I was never a labor goddess to begin with, far from it.)

It was a novel virus that dismantled lungs and vascular systems, economies and societies. As soon as the first cases hit the US, I knew in my heart we were in for at least a year of pandemic living. I also quickly realized my “birth-plan” (hilarious wishlists we make to provide the illusion of control over nature) would be vaporized pretty much overnight. It was instantly clear—I would be giving birth during lockdown, with zero answers on pretty much any virus-related questions, with only my husband attending, plus some masked midwives and nurses.

Well, there’s a story here, I thought.

Pregnancy is anxiety-inducing enough, but pregnancy coated in pandemic patina was a different beast. This was also a family story. There was precedence for this era, and poetry in it.

What started as a handful of poems written about my “pandemic pregnancy,” soon became an unintentional family history project.

My pandemic-born grandfather was both known to me and beloved, but I knew nothing about his mother, Alberta. She died young. And no living relatives knew much either, none had met her, no primary sources here to comb through. Then I got a tip from my oldest living aunt. Alberta, it turns out, was a poet. She was even published.

My pandemic-born grandfather was both known to me and beloved, but I knew nothing about his mother, Alberta. She died young. And no living relatives knew much either, none had met her, no primary sources here to comb through. Then I got a tip from my oldest living aunt. Alberta, it turns out, was a poet. She was even published.

Where were her poems? Nobody knew. No relatives had copies of them. I contacted the Mount Pleasant Historical Society, BYU, searched through The Relief Society Magazine archives, and the Saga of the Sandpitch literary journal. I finally found a lead at the University of Utah’s Marriott Library. An online search told me there was a folder in Special Collections with her name attached, along with a group of documents labeled “Poems.” The search result listed the names of some of them, including several that seemed to be related to motherhood. There were other folders, too. In one, an editorial written during the first wave of the 1918 pandemic. In another, an essay on mothers and babies published in a regional literary magazine.

Only one problem remained. I couldn’t access any of these treasures. The entire Marriott Library was closed, due to Covid. Even the Curator of Manuscripts didn’t have access to them, and couldn’t even digitize and scan them. Those 5 months of library closure were agonizing. They were as impatience-making as being pregnant.

Finally in September I got my hands on them. Some were typed, but many were written in her own hand, a lovely, measured cursive. They gave me insight into her experiences with pregnancy and mothering a newborn, and also connected her to me in some beautiful ways.

Finally in September I got my hands on them. Some were typed, but many were written in her own hand, a lovely, measured cursive. They gave me insight into her experiences with pregnancy and mothering a newborn, and also connected her to me in some beautiful ways.

There were poems about flowers, babies, essays about motherhood, childhood, loss, grief, and tumultuous joy. Editorials about war, disease, and human spirit. I felt her in a way people tell you you’ll feel when doing family history. It clicked.

What resulted is this collection of pandemic poetry. Our two stories, woven together to give a look at how little has changed in 100 years.

Mount Pleasant, December 1918

We all wore masks whenever we left the house and school was dismissed. No church services held. We all have succumbed, all of us, but Papa who has been spared. He tends to us with patient care. We have a course of calomel and a hefty dose of castor oil. Shredded wheat biscuits every day. Many townspeople died.

– James Jacobs, Alberta’s son

The house heaves.

Influenza has come, quick in its creeping.

Our family is a choir of coughing

and weepy wondered hymns.

I pray unceasingly for my unborn baby.

This flu is worse than expected

Is taking men young and old.

Grave news:

My sister Edith is fallen ill.

A craquelure of lungs. She lingers no more.

This virus cheats us of funerals.

No hams nor cakes nor verse.

There are abbreviated goodbyes and remembrances,

quiet rites.

I am not permitted graveside.

I say a prayer, I send up a goodbye

from a heavy distance.

My baby holds at peace inside, to mark my solemnity.

Edith, my forever sister, my Edith.

A message the angels will deliver in my stead.

Christmastime waits patient outside the door.

The baby will arrive presently.

The baby will need me in apt health.

So dispense, tears

steady me up, dear Sleeping Sister.

Though this particular poem is written by me (from her perspective and using the facts available to me) it was clear from her journals and correspondence she was equally unsettled by the haze of death that swallowed up a good chunk of brainspace, and that left many millions vulnerable and quite shook. Our stories became one story, the story of an enduring motherhood marathon. The histories were similar as well. The same politicized plagues, the same fears, the same mask battles, the same economic uncertainties, the same lockdowns and rallyings against those lockdowns, the same types of folks breaking lockdown to visit Utah soda shops (I guess soda is our ancestral vice). And most (and somehow least) surprising of all, the same poetic inclinations running through our shared bloodline.

Adrienne Cardon is a writer, designer, and creative director. She has presented on creativity and writing at ALT Summit, BONCOM New York, and Listen to Your Mother. She is a recipient of the Mayhew Creative Arts award in poetry, and her writing has been featured in Inscape, Segullah, and Times and Seasons. Her debut collection of poetry, And Still, Birth: Death and New Life in a Pandemic can be found here. The Kansas native currently lives in Utah with her four children and filmmaker husband. You can connect with her at adriennecardon.com.

Adrienne Cardon is a writer, designer, and creative director. She has presented on creativity and writing at ALT Summit, BONCOM New York, and Listen to Your Mother. She is a recipient of the Mayhew Creative Arts award in poetry, and her writing has been featured in Inscape, Segullah, and Times and Seasons. Her debut collection of poetry, And Still, Birth: Death and New Life in a Pandemic can be found here. The Kansas native currently lives in Utah with her four children and filmmaker husband. You can connect with her at adriennecardon.com.

.

I’ve read this a couple times now. I’m so glad this book exists.