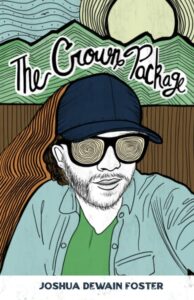

On Pioneer Day 2022, a July Sunday, I debuted my first book, The Crown Package: A Personal Anthology to a live-streamed audience and a handful of people in person. Thinking about who might attend, and also considering what I wanted to exist on YouTube, I’d prepared selections from the stories and essays collected in the book that wouldn’t bother anyone I thought might be in the room. The book, spanning my published and unpublished writing from 2005-2020, had plenty of examples of me being a Bad Good Mormon, but also many of me being a Good Bad Mormon. I wanted to deliver a reading that didn’t isolate or anger anyone, and certainly didn’t ruin someone’s Sabbath Day; namely, mine. This was my big debut, after all.

On Pioneer Day 2022, a July Sunday, I debuted my first book, The Crown Package: A Personal Anthology to a live-streamed audience and a handful of people in person. Thinking about who might attend, and also considering what I wanted to exist on YouTube, I’d prepared selections from the stories and essays collected in the book that wouldn’t bother anyone I thought might be in the room. The book, spanning my published and unpublished writing from 2005-2020, had plenty of examples of me being a Bad Good Mormon, but also many of me being a Good Bad Mormon. I wanted to deliver a reading that didn’t isolate or anger anyone, and certainly didn’t ruin someone’s Sabbath Day; namely, mine. This was my big debut, after all.

We held the reading in the ballroom of the Loft 745 Reception Center, where I live with my wife and co-editor Georgia Pearle. The Center is a big beautiful log building outside of Rigby, Idaho, and most of our business comes from BYU-Idaho weddings and other local member families. We live directly below the dance floor, in a basement apartment. I am a fourth generation Mormon farmer of pioneer stock living in the Snake River Valley, but Pearle, no Mormon heritage whatsoever, came here from the Gulf South, to be with me and raise our family together, and collaborate in the literary arts careers that we had long developed. In 2022, we published each other’s first books, Pearle’s poetry collection called Refinery, and mine, of course, the aforementioned Crown.

In attendance that day: my father and mother, who had just been released from being Mission Presidents in the Marshall Island / Kiribati Mission three weeks prior, my eldest sister and her Bishop husband, my youngest sister and her Stake Young Men’s Leader husband, and, surprisingly, a colleague from University of Houston’s Creative Writing Program that I’d never met who was in the area visiting her college professor parents vacationing in Driggs. My other three sisters and their husbands were on the live-stream, and a few others too, but by all measures, we were few.

I wanted no offense because literally everyone in the room except for the UH colleague was in the book, in some form or fashion, in scene or drama or dialogue. With my language and delivery, my content and vocabulary, now I had my living family to consider: my parents, my siblings, their impressionable kids, all my Mormon Facebook neighbors and friends proliferating the farms and ranches and chapels and MLMs up and down the Snake River and Wasatch Front, and not-to-mention my dead pioneer relatives, deceased Idahoan grandparents, who no doubt would be tuning in through the veil. But I also had to also consider my professional writer and editor network, folks from University of Houston, Stanford, University of Arizona, BYU-I, profs and friends and readers that I still wanted to entertain, if not impress. I did my best to make the reading an enjoyable and expletive-free hour, hopefully getting at some of the grit of my work, just less gritty.

After the reading, once everyone had clapped and stacked their own chairs, my father came buzzing up to me, his eyes big and kind, his face excited. He’s been a stoic potato and grain farmer his whole life, and I’ve always worked on the farm and ranch with him. I see him every day, enough to know how rare his excitement is.

“That’s what you’ve been writing all these years?” my father said as he took my hand and shook it, even grabbing my elbow with his free hand for emphasis. “Wow, I had no idea it would be good! I’ll take twenty-five, no, fifty copies! I want to send them back to all my friends on the islands, and all your aunts and uncles too!”

Sure, sure, I said. I mean, this reception pleased me; it was about the best actual response I could’ve hoped for. The family genuinely seemed pleased and entertained. But I knew the truth; I hadn’t been honest in my performance. I dreaded everything that I had read redacted or censored. Words I’d changed and thoughts I’d restricted. What would he say when he actually learned the truth?

I went to the farm the next day, Monday, always the worst day, and after our planning meeting, I pulled my father aside, had a pen and my farm notebook out.

“So how many books can I put you down for? A dozen?”

He did not look happy, and clearly had no time for literature.

“None!” he barked, “Your sisters got your copy and showed me you were lying about everything!”

I worked the rest of the day alone, minding my own business, belly-aching in silence. At home in the Loft basement, I poured it all out to Pearle, who listened to me bemoan my artistic plight, and ultimately suggested the seed for the new version of the book.

“Just make your dad a CleanFlix version,” Pearle said, wryly. “He’d love that.”

Pearle knew this would bedevil me. I started pacing the kitchen, agitated. Pearle was an Old Millenial just like me, remembering all too well the trips to Blockbuster and similar video rental business for media and art. As I had migrated Pearle to the West and educated her on our Jell-o Belt cultural paradoxes, I taught her about the Nineties era capitalistic and member-driven phenomenon of CleanFlix. It angered me deeply then and still does now, to think that all those Mormon guys had to do was chop out a few scenes of huge movies and then rake royalties and rentals. Off someone else’s art. I refused to partake. It didn’t help that no one around me felt the same way; it seemed like family and friends had no criticisms about the neutered narratives, they loved them, and would drive all the way to town to rent them.

In my own artistic quest, my pursuit has been to tell a good story that only I can, with no muzzling. To be honest on the page, and tell something true, real or not, make the reader see it and feel it, that was the goal. I wrote short stories and essays, sent them all out like mad to the magazines, landed pieces in great journals, including Dialogue and Irreantum. I edited for magazines too, Terrain.org and THE DIAGRAM and Gulf Coast, working through pieces with authors all the way to publication, championing individual expression, creation, and imagination. I collected my own best examples of this, I thought, in The Crown Package. Why would I backslide on that now and censor my own book? Pearle just kept smirking, knowing that she’d got me with something good.

The more I worried about the concept, the more I worked through layers, the more I fussed at the essayistic experimentation of it—well, pretty quickly the exercise seemed interesting and challenging. Would I change or omit? Rewrite scenes? Allude or preclude? Redact? I could make the book into one long Sunday Fireside, just another version of the truth. New creative questions and energy abounded, though I couldn’t do anything about it. It was harvest time by then. So for months, we cut the grain, dug the spuds, and brought the cows home. For months, I worked the scenarios in my mind, remembering once the first time I left the farm to become a writer, my mother pulling me aside and making me promise I wouldn’t cast my pearls before swine and out all the family secrets. Our stories were sacred, our memories special, and ourselves eternal. Books were the same way. As my mother always taught me: I needed to watch my mouth, bite my tongue.

Finally, through the winter, I tackled it, the labor taking five long winter months, ultimately producing The Clean Package: A Pioneer Assemblage released in March 2023. My father and mother took the first copies to St. George for their Spring Break. A true career highlight, for me, when my mother texted me a photo of my father reading the book. He finished it in a week, and told me about how much he enjoyed it, and the stories that stuck out to him, and how he understood me better now than ever before. I’d like to frame the photo, or post it—it is an all-time favorite—but I cannot. You see, my mother took the photo candidly, in secret from down the hall, and its intimacy may embarrass my father. So I will just have to describe it instead.

Finally, through the winter, I tackled it, the labor taking five long winter months, ultimately producing The Clean Package: A Pioneer Assemblage released in March 2023. My father and mother took the first copies to St. George for their Spring Break. A true career highlight, for me, when my mother texted me a photo of my father reading the book. He finished it in a week, and told me about how much he enjoyed it, and the stories that stuck out to him, and how he understood me better now than ever before. I’d like to frame the photo, or post it—it is an all-time favorite—but I cannot. You see, my mother took the photo candidly, in secret from down the hall, and its intimacy may embarrass my father. So I will just have to describe it instead.

My father sits in a chair, reading. Far away from the farm, he wears a golf polo, his legs are pale and exposed in golf shorts, and he’s barefoot, as naked and comfortable as he ever lets himself get. Silver-headed now, and with silver-framed glasses, he holds The Clean Package open with his left hand between his knees, and rests his chin in his right palm. He stares straight down into the pages, pondering, just like I always see him read his scriptures. It’s how I know he isn’t lying when he says that he likes it.

_________________

I have 5 free paperbacks of The Clean Package that I’d love to send out as a gift for curious AML readers. If you’d like one, message me, and we’ll make arrangements. I remain thankful to speak a unique language of a peculiar people, and to add my voice to a distinct and ever-evolving literary genealogy and geography.

The Clean Package: A Pioneer Assemblage is available for purchase at www.FosterLit.com and on Amazon in paperback and eBook format.

The Clean Package: A Pioneer Assemblage is available for purchase at www.FosterLit.com and on Amazon in paperback and eBook format.

Joshua Dewain Foster works and lives in southeastern Idaho. He earned a PhD from University of Houston in Creative Writing and Literature, was a Wallace Stegner fellow at Stanford University, and holds an MFA in fiction and nonfiction writing from the University of Arizona. Josh can be found on Facebook, Instagram, and X.

Id love one of those books.

Excellent! Email me a good postal address to

LitFosters (at) gmail . com

and I’ll mail out a book next week!

Sounds very interesting.

I’d happily send along a book for you to check out! Email me a good postal address to

LitFosters (at) gmail . com

and I’ll put it in the mail next week!