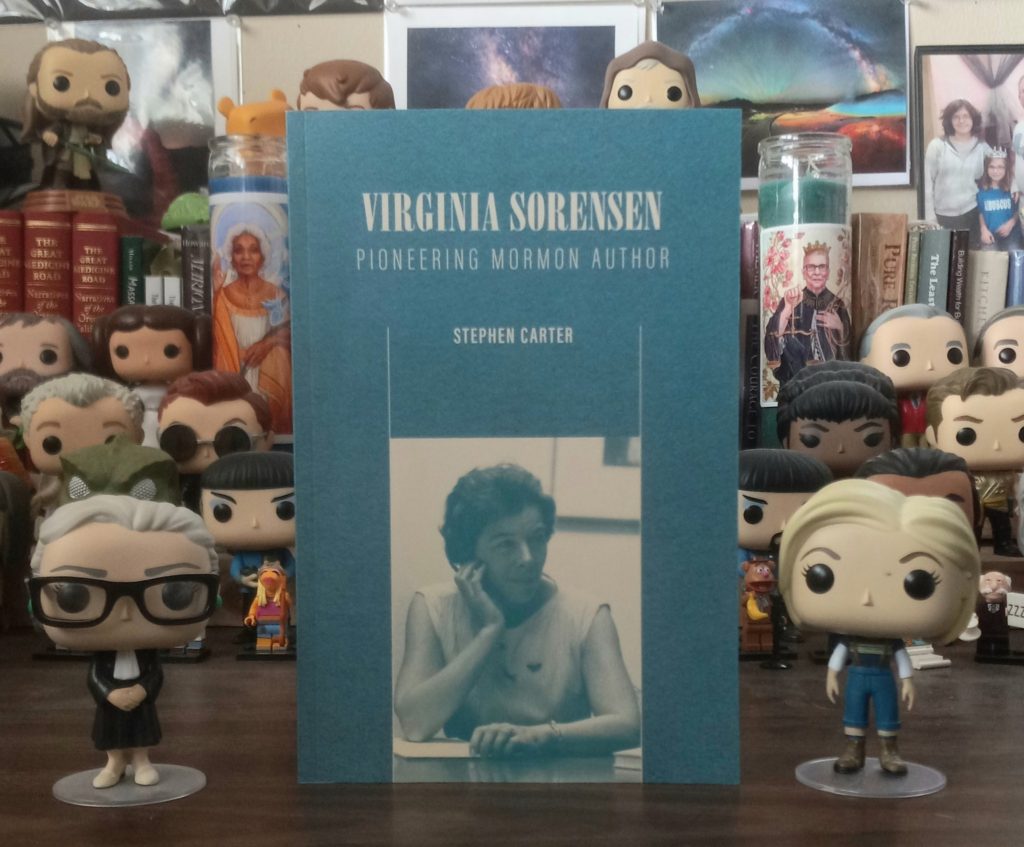

Title: Virginia Sorensen: Pioneering Mormon Author

Author: Stephen Carter

Publisher: Signature Books

Genre: Biography, History

Year Published: 2023

Number of Pages: 124

Binding: paper

ISBN: 978-1560854586

Price: 14.95

Reviewed by Adam McLain for the Association for Mormon Letters

Mormonism is no longer sequestered from the world, but rather the world is now in the midst of the Church and its members. What is a Latter-day Saint to do when faced with the burgeoning world at their doorstep? Step out and adventure into it, or retrench into the folds of conformity? Stephen Carter’s Virginia Sorensen: Pioneering Mormon Author argues that Virginia Sorensen, a twentieth-century author who was raised in and wrote about Mormonism, is the perfect literary example for our contemporary times of Mormon and post-Mormon. Her novels—especially her Mormon stories A Little Lower than the Angels (1942), On This Star (1946), The Evening and the Morning (1949), Many Heavens (1954), and Kingdom Come (1960)—present complex characters grappling with a childhood faith and the realities of the world. Her life shows someone who, despite divesting herself of Mormonism, still participated in the zeitgeist. For Carter, Sorensen is an example that can bridge a gap in understanding between those who have left the Church and those who remain; her literary characters bring to life the human struggles of staying and leaving just as much as her lived experience. As a petite, concise introduction to Sorensen and her oeuvre, Carter’s book achieves its intended purpose: it establishes the reader in a firm basic understanding of Sorensen and it entices them to actually pick up her works and discover if her characters are worth the merit provided by the historical record.

The book works as a brief introduction to Virginia Sorensen, her literary texts, and the conversation around those texts. It favors biography, which makes up the first seven chapters, but it also contains a chapter on the critical conversation around her works (chapter eight) and two chapters giving brief summaries and readings of her adult novels and her children’s books (chapters nine and ten). As part of Signature Books’ short biographical series (unified by design if not by name), it does its purpose well: as someone who has never read a Sorensen book and knew her only by name, I feel enlightened as to the highlights of Sorensen’s life, career, and legacy. Carter’s enthusiasm for Sorensen makes me even want to read her works and get to know her approach to Mormonism and life through her words (although, as with Carter, I too lament that the books are not easily available in print but rather just eBook).

Carter allows Sorensen to be seen as herself in the historical biography. Almost every paragraph of the first seven chapters contains a quote from a letter to or by Sorensen. Part of this means the book isn’t quite writing history outright but rather stringing together the documentary history of the subject. This is to the book’s credit because it does not seek to make anything of Sorensen; rather, it seeks to illuminate Sorensen vis-a-vis Sorensen. Carter’s goal, at least in the biographical chapters, is not to show Sorensen as something or someone—a debutante, post-Mormon, cosmopolitan woman nor a worldly, fallen-from-grace ex- or post-Mormon. Instead, in utilizing mostly Sorensen’s own words, Carter does a magnificent job of letting us get to know Sorensen through her personality and quirks; in some ways, I think he does what he believes Sorensen does in her books—presents a complex, human character through the written word.

Carter’s thesis with Sorensen—why Virginia Sorensen as an author should be considered and reconsidered in our contemporary world—is muted in many places of the text, which again emphasizes the role Carter seems to be playing as an author. This book is a brief introduction to Sorensen, not a monograph on her text (although now having read Carter’s book, I would love to see a monographic approach to Sorensen’s work). Carter calls Sorensen an “ethnographic novelist of Mormonism” (ix). Because of her upbringing and her lived experience, Sorensen was able to approach her childhood home of religion as both an insider and an outsider: in Carter’s words, she approached the complexity of the Church and the world “less as attacks on her soul and more as a new world to explore” (ix). For Carter, Sorensen “speaks with a unique urgency and clarity to twenty-first-century Mormons and post-Mormons,” being able to form a bridge of understanding between the two (x). While these points are encouraging, they are also made mostly at the beginning of the text and not explicitly shown in the historical recounting of Sorensen’s life and are hinted at in the critical chapters at the end. Although the book fulfills its purpose as introductory, it makes me long for a more in-depth, sustained argument about Sorensen’s place, her effect, and her literature.

Because of the similarity I found in both series, a moment must be taken to compare Signature Books’ approach to introductions and the University of Illinois Press’s complementary introductions on Mormon thought. I began Carter’s book having read Kristine Haglund’s work on Eugene England (Eugene England: A Mormon Liberal, 2021), and begun Michael Austin’s work on Vardis Fisher (Vardis Fisher: A Mormon Novelist, 2021). I expected Carter’s book to be similar to those two, but I finished Carter’s book with a greater appreciation for both series as complementary and parallel. Signature Books’ approach to introductions provides a greater span of historical introduction and seems to limit the engagement with the works created by the historical figures, while the Introduction to Mormon Thought series from the University of Illinois Press emphasizes the Mormon theology, philosophy, and thought presented within the written works. Whereas Signature Books’ approach is to introduce a lay audience to key figures in Mormon history, the University of Illinois Press’s works emphasize pulling out Mormon concepts from the historical works. As a reader of both series, I feel they each add to and expand the common knowledge of Mormon figures, and both can be used to expand our base of understanding, whether we are a newcomer to the history or a long-time student.

This means, of course, that Carter’s book should be used as an introduction to a historical Sorensen and her work. It works perfectly for someone wanting to know more about Mormon literature, an introductory course to Mormonism and literature, and a cursory example of a mid-twentieth-century, American, globe-trotting writer. While reading the text, I kept wondering if we’d discover arguments about Sorensen’s place in literature, her theories as approached through her books, or her views of Mormonism. Some of this is seen, but it is not Carter’s main objective to argue as a literary critic; rather, the book is meant to introduce and set a foundation by which other scholars can argue. Carter accomplishes this feat—and, I hope, we as literary scholars can utilize his accomplishment to come to better understand Sorensen, Mormonism, and literature.