Review

Review

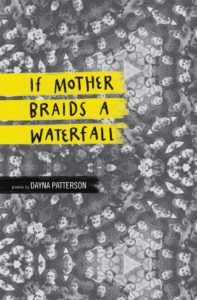

Title: If Mother Braids a Waterfall

Author: Dayna Patterson

Publisher: Signature Books

Genre: poetry collection

Year of Publication: 2020

Number of Pages: 118

Binding: paper

ISBN13: 978-1-560852803

Price: $10.95

Reviewed by Julie J. Nichols for the Association for Mormon Letters. June 2, 2020.

Years, years ago I wrote a poem with a line something like, “I can imagine a place/where it doesn’t matter/whether you’re Mormon or non-Mormon.” Something like that. I’d been living in Utah for a while—studying and teaching at BYU, mostly–and had gotten tired of how much it mattered. I grew up in the excellent northern California Mormon community, where diversity reigned, education was the norm, and world events were as familiar to conversation as the prophet’s latest decree (of which there weren’t that many, really, as I remember). Sure, we saw the birth of Correlation and did with it what we were supposed to, but mostly we thought for ourselves and drove to Salt Lake once a year to visit grandparents, have a family reunion, and come back home again.

If Mother Braids a Waterfall, Dayna Patterson’s first collection of the poetry she has published widely over the years in venues Mormon and not, comes out of, and is done with, a world where it really matters whether you’re Mormon. The titles in the Table of Contents intrigue: “The Mormons are Coming.” “Ode to Polygamy.” “Joseph Smith’s Death Mask.” “Brigham’s Wives.” “Post-Mormons are Leaving.” “Pioneer Day.” “We Christen the Canoe ‘Sunday School.’” “Still Mormon.” –and 44 others, most of them addressing the faults and irritations of a Mormon heritage. There is no indication where Patterson grew up (well—Wellsville?), but no question that it was in a Mormon milieu, with polygamous ancestors, a bisexual mom who left the family, and a dad who did double duty as a parent in much-appreciated ways. The poems tell that she served a mission in Canada, that she dearly loves her husband, that she has twin daughters, that she’s said good-bye to Mormonness and isn’t looking back.

Some of her lines are pretty prosey. “The Disposal of Mormon Garments” looks and sounds like a lusciously alliterative essay. In “Post-Mormons are Leaving,” many of the 32 stanzas allude to Mormon history and rumor but don’t exactly shimmer with metaphor or pattern of syllables or rhyme. Some stanzas do, though:

They’re leaving because conscience needles. Because/better angels prick. Because the path where they find their/ feet nettles, tricked with weeds.

These lines—like many others in the collection—swell with exactness of word choice, resonant images, sonorous juxtapositions. Photographs supplement the imagery, a kaleidoscope of women ancestors on the cover and the page edges, occasional portraits of Great-Great-Great-Grandfather Charles or a pedigree chart in pictures or a portrait of a grandmother.

Cleverness abounds, or its sister, intelligence in the form of surprising proximities. Notes in the back explain that “Still Mormon” borrows phrases from Dickinson and Keats (“I’m still Mormon the way a poem is a room/ and refuses the period’s lock”). Another entry in that same list of notes hardly needs to explain that “Former Mormons Catechize Their Kids” provides a moving parade of creation myth from many cultures, a directory of ways to account for our place on earth that don’t depend on the Mormon story. “Pon Farr” (59) and “Study for Belief with Lines from Star Trek: The Original Series” (93) employ the brilliance of science fiction for engaging imagination, emotion, and form as alternates to old, unquestioned stories.

One of my favorites in this collection is “Volvelle” (96). This set of tercets (eleven and two-thirds of them) marvels over an ancient device “meant to settle all/ religious disputes.” It reminds the poet of “brads and paper wheels/ the make-do of kindergarten teachers,” amazes her that this was “once labeled dark arts, shunned/ by skeptics.” The final lines hiss with her own skepticism, born of an upbringing fastened to prophets’ declarations:

…I whisper past glass, Prophesy/ to me, unwind, unfold, say which/ is which. Then I hold my breath,/ watch for the twitch.

It’s one of my favorites because it doesn’t directly name any aspect of Mormonism as an irritant. In this poem, Mormon or not doesn’t matter. Doubt and questioning are simply (or complexly, I mean) human. Historical.

If pointing to cultural and institutional foibles of Mormonism appeals, then this collection will be rich for you. Many poems have been published in Dove Song: Heavenly Mother in Mormon Poetry, Segullah, and the Dialogue “A Mother Here Art and Poetry Contest”; Patterson feels intensely the baldfaced exclusion of women from Mormon sacred stories. I do too, and I appreciate the ways her poems call out the littleness of much in Utah Mormon culture.

But poetry does its best work when it recognizes that human is complicated, varied, multi-layered, leaden as well as gold. Also when it rejoices in the forms—sounds, patterns, images—that reverberate in our viscera, echo our emotions. Patterson is at her best, I think, in poems that expand into form and content beyond Mormon complaints. When she’s writing about her husband; about her mother; about alternative stories—she shines like the sun. She’s braiding a waterfall.

This is a collection to chew on and wonder: how much does being Mormon matter?

Thank you for this thoughtful review, Julie. What a gift honest criticism is. I’ll be chewing on your last question for a good while.