Jennifer Quist is a writer, critic, and author of three novels. Love Letters of the Angels of Death (Linda Leigh Publishing, 2013) was long-listed for the Dublin International Literary Award, and was a finalist in the General Category of the Whitney Award. On its merits, she was named an Alberta Lieutenant Governor’s Emerging Artist of the year in 2014. Sistering (LLP, 2015) was given the 2015 Association for Mormon Letters Novel Award, and long-listed for the Alberta Readers’ Choice Award. Quist’s non-fiction is published in New Left Review, The Puritan, The Awl, Maclean’s, and The Globe and Mail and on CBC Radio. A graduate student at the University of Alberta studying Comparative Literature and Chinese, she lives in Edmonton with her family.

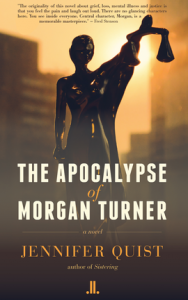

Jennifer’s third novel, The Apocalypse of Morgan Turner, is being released this weekend. Here is the blurb:

“Morgan Turner’s grief over her sister’s brutal murder has become a rut, an everyday horror she is caught in along with her estranged parents and chilly older brother. In search of a way out, she delves the depths of a factory abattoir, classic horror cinema — and the Canadian criminal justice system, as it tries her sister’s killer and former lover, who is arguing that he is Not Criminally Responsible for his actions because of mental illness. Whatever the verdict, Morgan — with the help of her Chinese immigrant coworkers, a do-gooder, and a lovelorn schizophrenia patient — uncovers her own way to move on.”

Rachel Helps has written a review of the novel, which will appear in an upcoming issue of Dialogue. Here is a selection from the review. “The Apocalypse of Morgan Turner is a short but carefully crafted literary novel, which gives readers a view into the impact continual court appearances can have on a victim’s family. Characters in the book contemplate the origin of evil and mental illness, as well as friendship and self-expression.”

Helps also conducted the following interview with Quist.

Part of this novel started as short stories. What made you want to turn it into a novel? Was it difficult to make the stories “fit” in with a larger story?

Part of this novel started as short stories. What made you want to turn it into a novel? Was it difficult to make the stories “fit” in with a larger story?

The book actually started as a book. I began writing it even before my second novel had been published and I always intended for it to be a novel. Two of its chapters became short stories mostly due to the practical limitations of the editing process. It’s hard to find a high quality editor who will read an entire book-length manuscript on my budget of $0 per page so I had to work around it. I partitioned the first short story–the one that was published as “Everybody’s Horror Movie“–for a creative writing class I was taking at the the University of Alberta where each student brought a story to workshop. The second short story, “Eye-Knack,” was cut down to meet the 15 page limit the university’s writer-in-residence would read. This story also had another life as something more like a performance piece I did where scenes from the real version of the movie referred to in the chapter were projected on a wall behind me while I read from the story in a campus pub. Through all of these smaller projects, the big, ultimate project of the novel remained my goal (especially since the project was funded by an arts grant [O Canada!] which was awarded to me based on the promise of a finished draft within one year). The logistics of editing aside, I find that short stories tend to be tighter and better written than long, loose, floppy, self-indulgent, self-important novels. They’re usually better grounded in reader responses and in genuine human experiences. Because of that, what I want my novels to be are good short stories of around 300 pages. One way to try to trick myself into writing like that is to put parts of the novel under the lenses of a short stories as part of the process of making them fit to read.

You’ve been studying Chinese intensively recently, and Chinese appears frequently in this book. It seems like at one point that Morgan can express herself in Chinese in a way she can’t in English. Why can she express herself more freely in Chinese?

Morgan hardly expresses herself in English at all. She is only quoted directly in three (I think) very short sentences. Her grasp of her native language is perfectly normal but it still doesn’t work for her. People use it to tell her things but most of the time, she can’t seem to get anyone else–her family members in particular–to let her tell them anything in return. It’s a stable pattern that she has stopped resisting except for during a few exceptional outbursts, including the one in which she is so desperate to be heard, she gives up on English–the language that never gets her what she needs–instead of giving up on the people who never give her what she needs. In addition to all of that, a new language makes everything new, and renewal is one of the functions of a novel–or it had certainly better be if the novel is touting itself as an apocalypse. I could get all Bakhtin here and muse about the heteroglossia of the novel and of Morgan’s character but–I guess I don’t quite have the cheek to try to write formal literary criticism about my own work.

You mentioned that The Apocalypse of Morgan Turner was partially funded with an arts grant. What was it like to have someone other than your editor invested in your work?

The Canada Council for the Arts only wanted a brief, one page report on whether the draft was finished by the end of the year or not. In return, I agreed to mention their contribution in the book’s front matter should it ever be published. To this day, no one from the council has read more than a proposal for the book–a proposal which I deviated from quite a bit when I actually sat down to write it. They cut me a cheque and the rest was up to me, which is appropriate since having an government funded body looking over the shoulders of writers and especially (ahem) journalists is contrary to the principles of free societies. Like all countries, we have abuses of power in our government, but tying the hands of creative people through the allocation of grant money is minimized by not making us accountable to the government for the specific content of our finished projects. So I guess what I’m saying is, the council’s investment didn’t have much of an effect on the book itself. It did just what it was supposed to do and freed my time for writing. I suppose the one-year grant period would have kept the project moving if it had stalled, but lucky for me it didn’t.

That sounds like a pleasant patron! Are there any people in your life who did have an effect on the book itself? You mentioned your family in your acknowledgements section, and your son filmed your book trailer. How involved is your family in your writing process?

My family is supportive and patient with me–showing up at events, bringing cake, and, yes, my big son did spend an entire afternoon shooting footage of the parts of our city where the book was set for our trailer. However, they aren’t involved in the actual writing. Ever since I was writing in leftover school notebooks as a kid, I kept them out of sight and never wanted to share my work with anyone until it’s ready–whatever that means. To this day, I’ll tilt my laptop screen downward if someone comes up behind me while I’m working, even if I’m writing in a language I know they don’t read. It’s just a reaction I have that’s beyond reason. I suppose I must like my work to gestate in the dark. It is true, though, that inspiration comes from what’s around me and that includes clever and poignant things family members say, experiences we share, things they teach me, and in that way their help is substantial. Still, none of them sees my novels or stories until they’re already in print. This time was a little different since the parts of the book set in the criminal justice system are best written according to actual legal practices and principles. It’s a background I don’t have so I tapped into the expertise of a family member who works in the courts. I had him read the courtroom scenes to catch any glaring errors. Oh, and for my first novel, I went to my returned missionary little brother to find out how to count to five in Tagalog.

What authors do you admire or recommend for your fans? Who do you write for?

By my “fans,” you must mean my dad. He’s retired now and devoting his time to grandkids, his cat, and yard work. I’m not a model reader to follow, certainly not since I went back to school. It’s ironic how little literature I actually get to read in the course of working on a doctoral degree in comparative literature. My reading lists are mostly heavy critical theorists with very little fiction. In fiction, I most recently read Lu Xun’s Diary of a Madman in the original Mandarin. It was an important and worthwhile read but–yeah, would not recommend most people I know. I did get to read some Mormon literature over the Christmas holidays–some good and some surprisingly bad. From that pool, I would recommend Steven Peck’s crazy Gilda Trillim… I almost gave up during the badminton tournament and the junk drawer but after I proved myself, I got to read the muskrats and rat-rats and the “So what?” and it was well worth it–astonishing, actually.

Rachel Helps is the Harold B. Lee Library’s coordinator of Wikipedia initiatives, where she contributes to Wikipedia pages related to their collections like Mildred Dilling and Lucinda Lee Dalton. She helped her sister, Andrea Landaker, write a newlywed relationship simulation called Our Personal Space. They are working on the sequel, Space to Grow, which focuses on raising children.