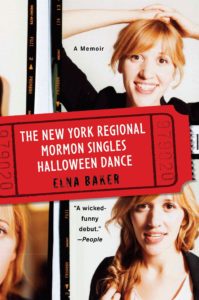

Had I made a mistake in picking Elna Baker’s The New York Regional Mormon Singles Halloween Dance (Dutton Adult, 2009) for my book group? I’d set the goal of reading LDS literature in 2021 and invited others to join me, because I was hungry for voices from my own culture. Despite holding a PhD in literature, I’d never encountered literature by someone of my own faith in an academic setting and had read little beyond a smattering of blogs and inspirational Desert Book selections. Baker’s memoir seemed like an obvious choice. Her experience as an LDS woman struggling to find love and a career in New York City dovetailed with my own history of meeting my spouse in Manhattan. More importantly, I wanted to understand why there are so few LDS figures in mainstream literature—how one could go through higher education and encounter only sensationalized polygamists or abused women depicted by non-Mormons, if any LDS figures at all. Reading one of the few contemporary books about LDS people to have found a home with a national publisher seemed like a good place to start. Yet when some friends began expressing discomfort with my choice, I turned to Good Reads to understand what I was about to encounter. The reviews were decidedly mixed.

The key fact about the Manhattan singles scene in which Baker sets her memoir is that eligible LDS women greatly outnumbered eligible LDS men, leaving quite a few LDS women with the realization that they would likely find themselves doing something other than marrying in the temple but without any guidance on what that alternative might be. Baker’s memoir is partly a product of this structural imbalance, exploring the shapes those alternatives might take as she dates non-members, struggles with her body image and occasionally takes risks that would make an orthodox Mormon uncomfortable on the road to professional success. Central to the story is the idea that potential alternatives to the Mormon marriage she can’t seem to find would require sexual compromises she is not ready to make. She ends the memoir without a partner and still struggling to resolve these tensions and find a place, an ending that feels both disappointing and true to the experience of many single LDS women in the city.

Baker is complicated: she is sincere while open about telling lies, anxious yet brave, faithful but questioning. She discusses topics like sex far more explicitly than in stories with which members are more accustomed, delving into situations that other LDS authors might be inclined to hide. As such, her mixed reception on Good Reads makes perfect sense. Many reviews are a litany of judgments, presumably by other members, about her choices or pronouncements that she does not understand her own religion. And, honestly, I get the impulse to compare and judge when encountering a memoir by a co-religionist, because it feels like your own life choices and image are on the line. As much as I thoroughly enjoyed her book, however, I left disappointed that it was yet another story in which an LDS heroine is depicted as being asked to choose between her religion and the relationships and professional opportunities held by the city. I am tired of facing this kind of deflating choice. I want so badly to believe that other kinds of plots are possible—plots in which being an LDS woman opens opportunities rather than results in renunciation of some aspect of life. I want affirmation that I can be an active member and a writer who finds support within each of her different communities. No one wants a heroine who reinforces rather than resolves the problems she recognizes in her own life.

While it’s hard to imagine non-LDS readers caring about this memoir given Mormonism’s present lack of significant cultural status, it seems clear that many LDS readers found the book dissatisfying, though for different reasons ranging from discomfort with discussions of sexuality to disappointment at Baker’s limited options. And that problem helps answer my initial question: why is there so little LDS literature? Reading the reviews, I sympathized with how difficult it is for LDS (or formerly LDS) writers like Baker to appeal to both an LDS audience (which is itself not monolithic) and potential national editors who often know Mormonism primarily through stereotypes and want something different than LDS writers and readers—if they are interested at all in a conservative religion headquartered in the mountain west whose public figures are white men and whose members no longer seem especially persecuted.

In Baker’s case, the story of what LDS women ought to do in the absence of a temple marriage is one with which LDS culture is not fully comfortable, even while such stories are desperately needed. It’s also a story in which many LDS members feel invested, and yet perhaps therefore more anxious to control how it is shaped. It’s difficult to imagine this kind of memoir being published by Desert Book given its implicit openness about the ways in which Mormonism is failing many young women, it’s honest discussion of how sexuality impacts marriage options, and a heroine who ends in an ambivalent place. However, I also found myself doubting that it would have found a national press had it not been more openly sexual than many LDS readers would like, because why else would non-Mormons find this peculiar cultural predicament interesting? The memoir, for example, is driven by the question of whether or not she will remain a virgin—a plot likely to turn off the majority of the potential audience even while making it seem more publishable to outsiders. Other contemporary LDS books that have found national acclaim are usually also sensational, though in different ways. Tara Westover’s Educated (Random House, 2018), for example, easily falls into the trope of a woman saved by education from an extremist family, while Mette Harrison’s The Bishop’s Wife (SOHO, 2014) is a murder mystery in which a bishop’s wife uncovers domestic violence and sexual abuse within her congregation.

So what should LDS writers do when they face a religious community that is often critical of their decision to publish their experiences and editors who often don’t understand Mormonism or view it as unpublishable outside a narrow range of tropes? Reading Baker’s memoir, I couldn’t help but link her plight as a single LDS woman in New York City with the similar but different problem LDS writers face when few seem to want what they have to say. And yet it is precisely more stories—more visions of what it might mean to live fully as a member of the LDS faith—that are needed to address problems like being a single, LDS woman in a city without marriage prospects. To some extent, our failure to support LDS writers who attempt to address such uneasy aspects of LDS experience perpetuates the inability of members to craft more expansive views of their potential options.

I put down this memoir recommitted to helping build a different literary market in which LDS writers do not need to replicate the narrative of “choice” between religion and success, either in their lives or literature. As LDS readers, I believe we must demonstrate that we are a viable, eager market by supporting our own writers if we want others to take us more seriously as an audience. Thankfully, there are growing forums in which we can do so: supporting independent presses and magazines targeted at LDS audiences, such as By Common Consent Press or Irreantum; attending writing workshops, such as the free craft classes Exponent II is currently offering; and not hesitating to highlight writing by LDS authors in our own books clubs and wards.

Natalie Brown holds a PhD in English and Comparative Literature from Columbia University. She is guest editor of Irreantum’s “Building Zion” issue on homes and houses in LDS culture and theology. She’d like to thank the members of her book club for helping her generate these thoughts.

Such great points you make here, Natalie. I do think we need a greater diversity of voices in LDS and LDS-adjacent literature. I don’t know how to change the minds of the big publishing houses, but I do think it is important to elevate the kinds of voices we want to hear more from via all the avenues you mentioned.

Interesting article! Thanks for reviewing the book. Your comment, “ I get the impulse to compare and judge when encountering a memoir by a co-religionist, because it feels like your own life choices and image are on the line,” rings so true! I find that any book set in a specific group risks alienating that very group for that reason! Very complicated.

Stopped partway through to read passages out loud to Nicole. Really great thinking. Amen.

I think about this all the time, that most often Mormon stories in the broader world come down to the choice of leaving and growing or staying and stagnating. My own book I’m trying to publish comes down to the same thing. I wish there were more space for stories about growth within the realm of staying. I do think people stay and grow! But usually their stories end up feeling like faith-promoting devotionals, not that these are bad at all, just a different kind of book.

This is an excellent point, Kami.

Well, really, there are very few outlets other than self-publishing to get a secular Mormon view out there in the mainstream. My own book garnered a starred review in Publisher’s Weekly, yet my goal–to put Mormon culture and vocabulary out to the public at large–still isn’t met.

This was a fantastic article, Natalie. Beautifully written and thought provoking. I very much agree with the conclusions you have drawn here and while I tend to steer clear of works written by LDS authors because of those common tropes you mentioned, I would be open to reading more of they wrote and thought more like you. I look forward to following your journey and career. Thanks for sharing.

Thoughtful piece, but there’s a factor here that’s worth considering when thinking about how the book got published. Elna Baker has an audience in the millions as a producer/performer for This American Life. Based on what I’ve heard from her, I suspect a lot of the memoir was drawn from pieces she worked up for the show. Or maybe the last piece I heard was drawn from the memoir.

Thoughtful post. There is a wrinkle, though, in relation to the book getting published. Elna Baker’s name and voice are probably familiar to millions from her work on This American Life. So there’s a ready audience for the book. The last piece I heard from her was about her decision to break from the Church, and sounds like a follow-up to the memoir. I suspect the memoir and her work for Ira Glass feed off each other.

Looks like I should have refreshed my browser before rewriting the comment that didn’t show up. The dangers of trying to write for your own group are not limited to Mormons, though. Every group has its sore points. I remember Peter Sagal saying he found out one of his culture’s pain points when he wrote a play about a holocaust denier. Not that he’s a holocaust denier in any degree, but the subject is very emotional.

Thoughtful perspective, Natalie. I love your goal to read and promote more LDS literature in 2021. As a fan of memoir, it was a pleasure for me to discover Baker’s memoir years ago—a work that openly discusses her faith, religion, and individuality. (I would have gladly been part of your book club.) I was excited to discover a nationally-published work by a Mormon about her Mormonism that had nothing to do with polygamy.

Perhaps the “fault” for lack of traditionally published Mormon voices rests partially with Mormon authors???? Or maybe just me. For example, in my attempt to make Lies of the Magpie accessible and nondenominational, the first manuscript I sent to my editor skimmed over my faith and religion, leaving out any mention of Mormonism. My wise editor—not a member of the church—said it felt inauthentic and requested a rewrite which included faith and religion. That rewrite was HARD! It was far easier to write leaving out religion than to find words to normalize and make accessible things that are deeply personal and challenging to explain, but the end result was a more authentic, more honest, more readable and believable memoir. What if my editor hadn’t nudged me to include faith?

The onus is in my hands, I think, to step up to the challenge of writing what at time feels “unwritable” and to create a voice so compelling and so authentically human that the reader only notices the “mormonism” because it so naturally belongs in the story.