A guest post by Steven L. Peck.

A guest post by Steven L. Peck.

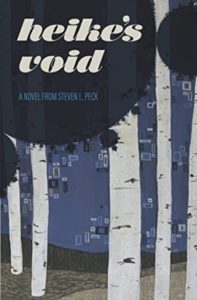

Heike’s Void is my most deeply spiritual book. An odd claim for a book that begins, “There are those God hates.” The book problematizes many things we take for granted and trivializes other ideas we take with profound seriousness. Much about the book plays with such paradox, and to get at the spiritual underpinnings one must move all the way through the book and look at its overall shape. In my experience, the soul of literature worth reading always explores questions. And I mean this broadly including works written for entertainment. One of the greatest explorations of questions ever written was Buffy the Vampire Slayer (e.g., look at Jana Riess’ book, What would Buffy Do, if you don’t want to take my word for it.) Answers are dreary. Offering solutions only demands the most tedious work-a-day efforts for both writers and readers. When I used to do proofs in my graduate mathematics classes, it was the questions one asked that in the end reveal the solutions that led (At last! Eureka!) to the completion of the proof. After recognizing the right questions sketching out the details of the proof were usually boring and required analytics that any computer-based approach could manage. The real human work was the creativity and artistry that went into the questions. I remember once I spent four hours on the phone with my son taking a Real Analysis (the study of the properties of real numbers) advanced math class. Most of that time was spent in silence as we worked together to find the questions that would pull us into finding the proof. There was a math joke my professors would tell about the mathematician who said, after claiming she’d solved a proof without writing anything down, “I see there is a solution, the rest are just details for someone else.” So, questions are where I want to end up when I read and write. So, before I get at some of the questions Heike’s Void explores. Let’s talk Mormon literature. Always fraught. Fools rush in and all that.

In a discourse published in the Ensign, called “The Gospel Vision of the Arts.” President Spencer W. Kimball runs through his list of the great art, literature, and music of the world and asks, “Could there be among us embryo poets and novelists like Goethe? . . . There may be many Goethes among us even today, waiting to be discovered. Inspired Saints will write great books and novels and biographies and plays.”

There have been several truly great books that have come from my people. I suspect more will emerge. I won’t name them here because I don’t want to start a debate about who’s writing great Mormon literature, some of the writers I would name are my friends, and it is always dangerous to name names because every list created is also a list of who is excluded. However, I do want to start a debate about what makes great literature of any stripe. Not in the service of claiming I write such, but that is the target of my pursuit no matter how far I fall from the mark.

To think about great literature, let’s go back to the greatest discourse on the subject ever written. I refer of course to is the 5th Century Chinese monk Liu Xie’s The Literary Mind and the Carving of Dragons.1 The modern scholar, J. Zhang, wrote a treatise on Liu Xie’s use of the concept of Shen Si, the soul of (atheistic) creation.2 This is not a series of techniques as might be described as a set of instructions or rules, but rather an atheistic based on a sense of wholeness through which the entire work is striving for something whole and meritorious. However, this is not holistic in the sense of parts cobbled together to create a single complete structure, but rather associated with the “Wu” meaning nothingness or the Taoist concept of nothingness or the void3 in which creativity has its origin in silence and emptiness. It is an organic structure that emerges (in the modern sense) much like a living thing (and who would dare claim that great literature is not a living thing?). This wholeness requires knowledge, expression, curiosity, and doubt, all the things we associate with great writing, but the most crucial aspect of creating this literary mind is the engagement with questions. Insoluble questions. Not contrived questions. Not questions we already know the answer to, or want to put forward a position we already have committed to and want to convince another of our inherency, but questions that disturb our dreams. That frighten us. That partake of, and stand before, the terror of the sublime inexpressible. Liu Xie, then argues for an aesthetics that creates an emergence of creative, ethical (including rightness connoting the beautiful and justice), and profound engagement of human (add Mormon) existential concerns about our relationship to others and the cosmos.

So secondly, to fulfill President Kimball’s vision about Mormon Literature, we have to move out of the realm of thinking about writing great literature and to think about readers of great literature. We need a people ready to read questions. To be disturbed. To be rattled and twisted out of their hammocks (speaking personally), and be ready to receive unresolved questions, perhaps unresolvable questions, rather than answers. Questions that lead to more questions. This is how knowledge progresses. It is a series of questions, not answers. I think of the publication of Moby Dick and To the Lighthouse. Unquestioned books of genius but received with public “meh.’ Why? Great literature like Melville and Woolf’s were ignored because there were not readers prepared for the questions that they splashed into reality. I believe the great literature of Mormonism is not just waiting for great writers as Pres. Kimbell suggested, but it’s waiting for a people ready for great literature. We need both. If we are not ready for questions, and writing that serves only answers, we will not be a people who are ready for great literature. As the philosopher Deleuze writes about two series meeting, like writers and readers prepared for each other, he says, “Something, ‘passes’ between the borders, events explode, phenomena flash, like thunder and lighting.”4 I think about Walter Benjamin’s idea of the messianic in historical research. The appearance of an idea destabilizes and breaks the totalizing influence that locks history into a static mannequin of the past. As I read it, the messianic, which opens the world, is always about questions. Not answers. And as likely as not the messianic will not be recognized as such, until a people appear who are ready.

I need to clarify one thing; this idea often devolves into the notion that talking about questions and answers will be mistakenly construed as an argument about doubt and belief. No. I’m not saying that. Anyone who believes they, we (plug in your favorite diatribing perspective) have the answers, and the other perspecive (usually the photographic negative of my views where my light hues are your dark colors), is wrong, have lost the narrative and fallen into the abyss. This, whether they are Mormon (a tradition writ larger than the Church) or post-Mormon, or whatever. If someone thinks they have all the answers, they have given up on the quest that great literature is trying to send us on. Like the turtles stacked in Yurtle’s sky-reaching cohort and whose backs ultimately support the elephants on which the cosmos rides, in every advance of knowledge, it’s questions all the way down. David Whyte suggests why they matter:

The way I interpreted it was the discipline of asking beautiful questions and that a beautiful question shapes a beautiful mind. And so the ability to ask beautiful questions — often in very un-beautiful moments — is one of the great disciplines of a human life. And a beautiful question starts to shape your identity as much by asking it as it does by having it answered. And you don’t have to do anything about it, you just have to keep asking. And before you know it, you will find yourself actually shaping a different life, meeting different people, finding conversations that are leading you in those directions that you wouldn’t even have seen before.

So Heike’s Void.

It is a book of questions. It will be up to you to decide if the questions it offers partake of the vision I just outlined or if it is just a slanted embrace of answers that devolve it into kitsch. But here are some of the things I think are worth talking about.

A void stands at the book’s center and structures its plot and course, including a void of answers. My books are perplexing to me because I understand their meaning no better than any other reader. They have no moral, and they are not written to expound an idea I embrace (this needs some nuance; another time, I’ll offer some thoughts on how well we know our own aims and influences). Nor do they offer advice on life and living. Or teach a principle. They reflect my theological conviction that God has no plan for our lives (if he had one, I long ago thwarted it with my aimless choices and poor judgment—a trait my characters share), only desires that we live meaningfully. God provides the capacity for music, but we are to fashion our instruments, learn to play them, develop their score and themes, and improvise freely, considering the other players and contingencies that emerge. Our lives are a work of art we offer back to God. Evolutionary biology has taught me that we do not live in a deterministic universe but one of chaos and randomness. Mind you, there are regularities like those that allow us to sail: winds, tack, and knowledge that will enable me to navigate on the ocean of this fragile existence. And the Gospel has taught me I am a free agent. But all and all, my theology is grounded in the notion that we are here (not just here on Earth, but here in existence) to create both meaning and beauty. In the book, the characters take on a life of their own. I watch with both delight and fear at what unfolds. As a panel held at Writ & Vison noticed about the book, I love my characters. They have their free agency. But questions unfold as my characters face existence are worth considering. Let’s look at two sets of question you might ponder as you read. First: What role does randomness play in our lives? Would you have married who you would have if you had not gone to that party? That chance meeting at a seminar that affected everything downstream? Do heavenly beings partake of a novel universe in which their choices matter and effect the outcomes of their eternal lives and those around them? How do God’s choices affect us? How have they affected us? Is agency and choice a condition of existence? In Mormonism Satan tried to take it away, what if it was not only a bad plan, but was an absurd plan, because it was impossible? Agency is part of life itself. To live is to act in the world—even for bacteria.

Secondly, a set of questions revolve around the opening statement, “There are those God hates.” Is that as absurd as it sounds? Is it any more absurd than the statement, “There are those God loves?” This gestures to the debates about conditional and unconditional love as if that were the only allowable dichotomy—a pointless debate. If love is just a condition of existence for God, then it is nothing more than a void into which anything can be writ. But what if God chooses to love? What if God is not love, as we often interpret the statement, “God is Love” and end with that, but if God loves us, God’s creation, not because it is just God’s nature to love, but because God is an agent that chooses to do so?

Last, for a moment consider this poem, a version of which is found in my poetry collection, Incorrect Astronomy:

I. God is far too complex to understand. Too intricate. Too magnificent. Too cold and pitiless like the blank places between galaxies. Hotter than the nuclear engines of massive suns. Too far. Too close. Neither microscopes nor telescopes can contain, compress, nor bring God near or drive God away.

II. God can be cruel and unbending, like the eyes of a wolf or the blood-covered jaws of a lioness. God is unrelenting in pursuit. God follows you into darkness or light. God sticks to the trail and if you pause and listen you will hear Her breathing close behind. There is no escape. God is a predator.

III. To focus on one detail or one process—one leaf, or the vain of a leaf, or the cells on the vain of a leaf—obscures, and forces God into a box into which He will not go. God is wild and cannot be tamed or made to fit in any cage.

IV. God cares for Her own. Like the mother crocodile Her carries his offspring from the sandy shore where they peep and cry to the river—where they flourish in abundant flowing water.

V. God is beautiful. Beautiful but very dangerous.

VI. Sometimes God scatters its influence far and wide hoping it will find a home like the eggs of a parasitic wasp laid deeply in the flesh of a hapless caterpillar. Some eggs are lost, but some go on to hatch, pupate, escape the host, become an adult, and search for their own host. God is a parasite.

VII. God goes on and on. He can be damaged but never stops. Just as Spring follows Winter, God rides cycles and cycles within cycles.

VIII. God can be scarred and has been. Only slowly does mending take place. Sometimes it takes eons. There are things God has never recovered from—cannot recover from.

IX. God can be studied, but you can’t control all the variables and what you find in the laboratory will be much different than what you find in the field.

X. To experience God you must immerse yourself in God. Quiet all other voices and flee anything of your own contrivance. Then, in the stillness of thunder and the hush of crickets you will feel God—more or less.

XI. There is no crack so small that He cannot not invade. No barrenness that can long withstand God. He comes on the wind, on the waves, from every direction. Like the first seeds arriving on the gale after the emergence of a volcanic island scouring or the wandering flies after a flood. Even great wastelands cannot long withstand His healing.

XII. On peaceful days, God sits and chews on His creation. He chews over the birthing of our bright universe. God chews and chews and chews. Sucking sweet juices from abundant grasses. God is a herbivore.

XIII. God is all around you. Out your window you can see God, or in high corners you can see where She builds a small web. Brush it away and she builds another. He can never be completely dismissed–you are part of God, part of the fragile threads that She watches patiently from his hiding place.

One question Heike’s Void explores is number II in the poem above: God’s relentless pursuit. And the demands of the radical agential love of God. And the agential chosen love expected of us, whether human or heavenly beings, if we are to be followers of God.

1. Lui Xie. 2015. The Literary Mind and the Carving of Dragons. Translated by Vincent Yu-Chung Shih. The Chinese University Press with New York Review Books. New York.

2. J. Zhang. The Soul of Creation (Shensi). Translated by Liquing Tao, Palgrave MacMillan, New York.

4. Deleuze, G. 1994. Difference & Repetition. Columbia University Press, New York.

Steven L. Peck is a Utah native from Moab, Utah, and currently lives in Pleasant Grove. He is an ecology professor at Brigham Young University, publishing in the fields of insect evolutionary ecology, ecological mathematics, and philosophy of biology. He is an author of novels, short fiction, and poetry, which explore relationships with science, religion, evolution, consciousness, and the ways humans interact with the other inhabitants of this planet. He is a two-time winner of the Association of Mormon Letters Novel Award (The Scholar of Moab, 2011, Torrey House Press; Gilda Trillim, Roundfire Books, 2017), and once for short story (Two-Dog Dose, Dialogue 2014). He was awarded the 2021 Smith-Pettit Foundation Award for Outstanding Contribution to Mormon Letters.

Steven L. Peck is a Utah native from Moab, Utah, and currently lives in Pleasant Grove. He is an ecology professor at Brigham Young University, publishing in the fields of insect evolutionary ecology, ecological mathematics, and philosophy of biology. He is an author of novels, short fiction, and poetry, which explore relationships with science, religion, evolution, consciousness, and the ways humans interact with the other inhabitants of this planet. He is a two-time winner of the Association of Mormon Letters Novel Award (The Scholar of Moab, 2011, Torrey House Press; Gilda Trillim, Roundfire Books, 2017), and once for short story (Two-Dog Dose, Dialogue 2014). He was awarded the 2021 Smith-Pettit Foundation Award for Outstanding Contribution to Mormon Letters.

This post helps me to understand a little better the depth and breadth of contemporary Mormon literature and thinking. I particularly agree with the premise that works of literary art are firstly organic works in nature. We writers merely cultivate stories and poems that come to us from devine inspiration, in my view. What makes excellent Mormon literature? That which is revelatory of Truths that have a certain moral or ethical bent. At the same time, we as LDS artists have a profound duty to espouse and expound that which is revealed to us in our Gospel as revealed to us from Jesus Christ. Each spiritual-based artwork (literary included) is an extended prompting from God.

.

This is hardly a helpful comment, but, me, I don’t like making lists because they tend to reveal what I have not read / did not understand.

adding “God is a predator” to my religious horror moodboard