The following is an excerpt from Randy Astle‘s new book, Mormon Cinema: Origins to 1952. Mormon Cinema is the first single-author book to comprehensively treat Mormon film in all its components. The result of nearly two decades of research, it deals with Mormon cinema in greater depth, both historically and theoretically, than any publication has done to date. It covers the complete history of Mormon cinema, from its roots in the 1800s to 1952. The book is published by the Mormon Arts Center, and is being released in conjunction with the Mormon Arts Center Festival, being held June 28-30, at Columbia University and Carnegie Hall, New York City. Randy will be speaking at 10AM on June 29.

The following is an excerpt from Randy Astle‘s new book, Mormon Cinema: Origins to 1952. Mormon Cinema is the first single-author book to comprehensively treat Mormon film in all its components. The result of nearly two decades of research, it deals with Mormon cinema in greater depth, both historically and theoretically, than any publication has done to date. It covers the complete history of Mormon cinema, from its roots in the 1800s to 1952. The book is published by the Mormon Arts Center, and is being released in conjunction with the Mormon Arts Center Festival, being held June 28-30, at Columbia University and Carnegie Hall, New York City. Randy will be speaking at 10AM on June 29.

[This section follows a section which discusses how Mormon artists and artisans were willing to embrace new techniques in the late 19th century].

There were also other devices more commonly seen as proto-cinematic that Mormons began to use in the years leading up to 1895. A family of handheld or tabletop optical toys that presaged cinema was immensely popular in the Victorian age, beginning with the thaumatrope in the 1820s and including the praxinoscope, phenakistoscope, stereoscope, zoetrope, and stroboscope. With the exception of the stereoscope, which produced a static three-dimensional effect, each was based on the twin principles of intermittent motion and persistence of vision: when images are presented rapidly but distinctly the human eye and brain merge them together or perceive them as one continual “moving” image; this is how film and video still operate today. The early toys generally featured a variation of a spinning disc with multiple drawn images and some kind of slot or viewing device to provide the necessary visual break to cause the images to appear to move rather than blur together. As private entertainments, devices like these did not warrant mention in the press or even necessarily personal journals, thus making it difficult to gauge how extensively they were had among the Mormons in the west, let alone those who lived in the eastern states or Europe. It could be assumed, though, that Mormons were just as eager as others of this era for new visual and narrative amusements, and as with all eastern merchandise their usage in Utah almost certainly increased after the arrival of the railroad.

With that said, it seems extremely unlikely that there would be many optical devices created with Mormon subject matter, and to our knowledge there was only one, released in 1904, nearly a decade after the advent of cinema, when the New York firm of Underwood & Underwood produced the stereo view of “The Latter Day Saints’ Tour from Palmyra, New York to Salt Lake City, Utah through the Stereoscope.” Like a modern children’s 3D view finder, the stereoscope, stereograph, or stereo view was basically a binocular eyepiece with each lens focused on one of two slightly offset images of the same picture; these combined to create a three-dimensional effect. At the turn of the century Underwood & Underwood was one of the largest creators of stereoscopes and stereoscopic photographs in the world, creating popular boxed sets of exotic locations in their “Travel System” series. “The Latter Day Saints’ Tour” featured thirty-eight views by photographer James Ricalton of everything from the Smith family farm in Palmyra to swimmers in the Great Salt Lake, all taken three years before George Edward Anderson’s better-known photographic tour of historic Church sites. Sales were apparently sufficient to prompt Underwood & Underwood to commission Seventy and Assistant Church Historian B. H. Roberts to adapt one of his recent books into a 132-page booklet to accompany their images. Through its choice of subjects, its depiction of Mormons as typical middle-class Americans, and the inclusion of the well-respected Roberts’ writing, “The Latter Day Saints’ Tour” represented a major softening of the public portrayal of the Mormon story—indeed, with it the Mormons became “the only religious group . . . to have a pictorial history in stereo”—and it was certainly the first instance of Mormon media produced at such an expansive scale.

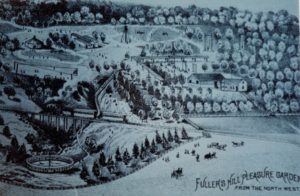

Although we know little about the Mormons’ use of small optical toys, there is more information about larger proto-cinematic technologies. The camera obscura, for instance, is a darkened space with a pinhole opening in the wall or ceiling, with or without a glass lens, which projects a view from outside onto a wall or the floor; the camera, which is Italian for chamber, could be a small box or, perhaps more commonly, an entire room capable of holding a group of spectators along with the projected moving image. It became popular as an entertainment after the 1500s, though its invention arguably dates back to ancient Greece and China. There is no known camera obscura in the Mormon settlements prior to the 1880s, but it seems likely Church members would have encountered them in Europe or east of the Mississippi, and it is also possible that unknown temporary structures in Utah were assembled and dismantled in a single carnival season. The first known camera obscura in the state, however, was an apparently permanent one at Fuller’s Hill Pleasure Gardens, a Salt Lake City fairground just west of the present-day campus of the University of Utah.

The park was opened by William Fuller, a British convert to the Church, in 1875, and while he might have constructed the camera obscura in that decade we know for certain that he was advertising it for the Independence Day celebrations of 1880. An 1887 illustration of the resort seems to show the camera obscura standing near the eastern edge of the grounds, somewhere close to the present day 1300 East and 200 South. Though patrons could enter the structure we don’t know its exact scale or dimensions or the object of its view, although it seems from the illustration to have a used a periscope-like turret common in more advanced camera obscuras that would have projected straight down onto the floor or a table in the center of the room. Various holes in the turret could have pointed in different directions, making it possible to have multiple views of the fairgrounds and the nearby city streets down the hillside. The camera obscura was mentioned in the press again when the park opened in May of 1881 and 1882, and improvements made in 1882—a “New and More Powerful Lens” and “New Power Fan . . . to Reduce the Heat”—imply that Fuller hoped it would remain at least for the imminent future, so it probably lasted until the federal government took over the property in the 1890s as part of the negotiations to achieve Utah statehood. Still, for over a decade the attraction was situated squarely in the world of the carnival: the park’s ten-cent admission price provided entrance to the camera obscura and the 400 views of the stereopticon—if the patron didn’t opt for the shooting gallery or four tries at the carnival game “Aunt Sally” instead.

This double bill of the camera obscura with the stereopticon, in fact, points to the most common type of proto-cinema among the Mormons: the magic lantern. Dating back at least to the 1600s, magic lanterns were akin to twentieth-century slide projectors: painted images on glass slides were illuminated by flame, gaslight, or electric bulb onto a screen while a narrator told a story or expounded on a factual topic. By the mid-1800s a dual-lens system known as the stereopticon allowed for easier effects like dissolves and superimpositions between two slides. Lanterns bore an obvious resemblance to the earlier painted panoramas but, as mentioned in Philo Dibble’s case, reduced cost for presenters and allowed for greater mobility, as well as mechanical reproducibility and the option to display photographs as the technology to print photos on the glass slides improved.

Religionists took strongly to the format as lanterns gained popularity in the 1800s, and Terry Lindvall identifies several points of synchronicity between this brand of proto-cinema and nineteenth-century Protestantism. As mentioned in the Introduction, John Fallon’s work as a traveling exhibitor of panoramas and stereopticon lectures was funded by the Central Congregational Sunday School in Massachusetts; others like John Stoddard, Burton Holmes, Joseph Boggs Beale, and Lyman H. Howe followed in his footsteps, and by the time magic lanterns hit the peak of their popularity innumerable presentations featured religious content, including productions of Quo Vadis, The Pilgrim’s Progress, and Ben-Hur. In Utah, Mormons weren’t the only ones exploiting the medium: Presbyterians, Unitarians, and others all presented regular lantern lectures on religious and secular topics, sometimes in bi-weekly series. But the most enthusiastic adopters of the technology were Utah’s Congregationalists, as described—and contextualized—by the Mormon-operated Provo Evening Dispatch in 1894:

“The stereopticon has come to be a recognized adjunct of religious work. In some of the largest churches east it is used with success, in both regular and other services. Beautiful pictures, reproductions of the nest works of art in existence, can thus be made to lend a charm and power to genuine gospel work which would not be possible by other means. Such use of the instrument is yet a novelty in many places but it is none the less wise and effective for that, if properly done. In the services now being held nightly at the Congregational church, Rev. John D. Nutting of Salt Lake, makes use of the stereopticon in varied ways for both pictures and hymns. Tonight at 7:30 there will be an illustrated service of song for half an hour followed by the sermon and other parts of the service. A most hearty invitation is extended to all.”

It appears that Reverend Nutting’s lectures were the tip of an iceberg. The Salt Lake papers of the 1890s are replete with notices of Congregationalist magic lantern events, including frequent lectures at their school building Hammond Hall and main church building at Independence Hall, with secular topics—astronomy, geology, and a trip through Yellowstone, for instance—receiving as much attention as the sacred. It seems from the Evening Dispatch’s language that the Mormons in Utah observed the Congregationalists’ actions with admiration if not jealousy, and this surely helped increase the frequency of their own lectures, although they had tentatively begun first using the medium much earlier.

Once again, we have no way of knowing when the first magic lantern presentation was given by a Church member or to a Mormon audience. It seems reasonable, however, that as with panoramas and camera obscuras Mormons would have been quite familiar with the format long before producing their own slides—and that they nearly certainly first encountered it in the east. Dibble’s 1878 use of the magic lantern, not long after the stereopticon’s invention, is perhaps the first recorded instance of the medium in the Church, but its popularity in the mountain west probably increased gradually with the modernizing effect of the completed railroad in 1869. What we do know with complete certainty is how enamored Mormons became with the medium. Magic lanterns were apparently common enough that in March 1887, less than a week after the Edmunds-Tucker Act required prospective Mormon jurors, voters, and public officials to take an oath denouncing polygamy, the populace adopted the term “swallowing the rat” from “The Ratcatcher,” a popular lantern show, to describe the act of taking the oath. That magic lanterns could so permeate the culture as to influence Mormon vernacular during the anti-polygamy raid is fascinating.

This begins to show lanterns’ influence among Mormons in the years immediately preceding cinema, but Mormon interest in the medium remarkably lasted for another hundred years.

Randy Astle received a B.A. in film, emphasizing screenwriting, at BYU in 2002 and a British M.A. (the equivalent of an American M.F.A.) in film production at the London Film School in 2006. A native of Salt Lake City, he works in New York as a screenwriter, director, editor, and journalist for Filmmaker magazine. He has been involved with Mormon film studies since 2001 and has published or presenting over thirty articles in BYU Studies, Dialogue, Sunstone, Irreantum, and various Mormon studies conferences.